Timeless Elegance of China Finds Its Reflection in These 10 Famous Chinese Artworks

- 1. The Nymphs of the Luo River, Gu Kaizhi

- 2. Yan Liben, the Tibetan Envoy, is received by Emperor Taizong

- 4. Han Huang - Five Oxen

- 5. The Night Revels Of Han Xizai – Gu Hongzhong

- 6. Wang Ximeng - A Thousand Li of Mountains and Rivers

- 7. Zhang Zeduan, Along the River during the Qingming Festival

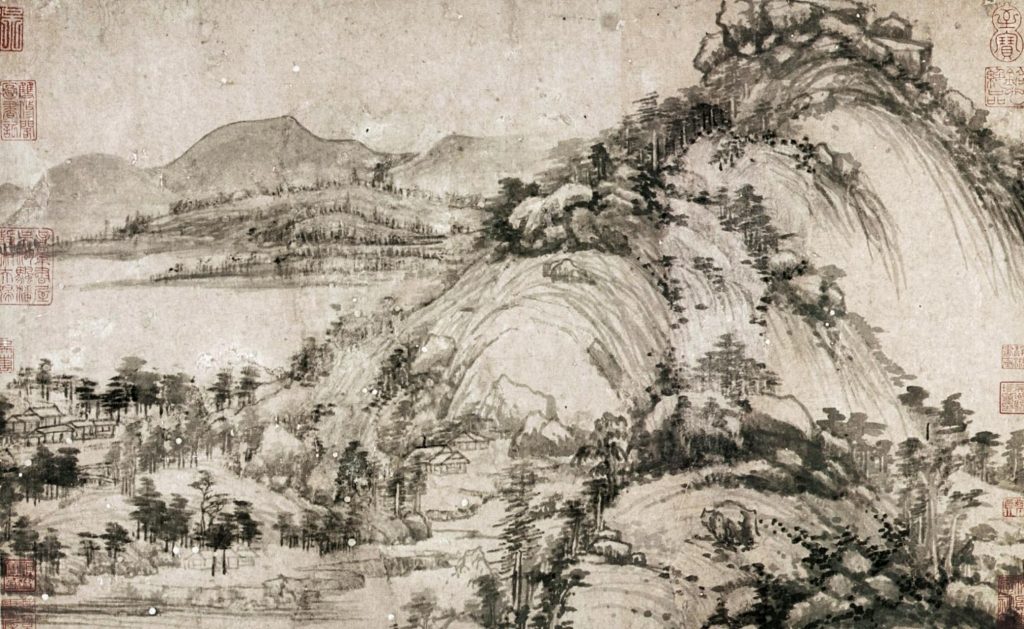

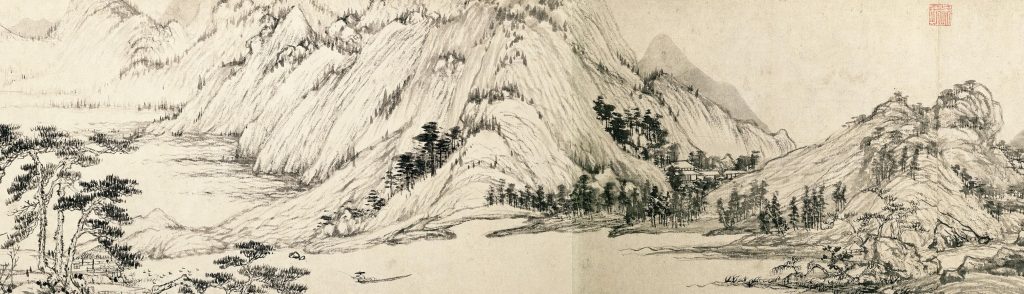

- 8. Huang Gongwang: Dwelling in Fuchun Mountains

- The Remaining Mountain

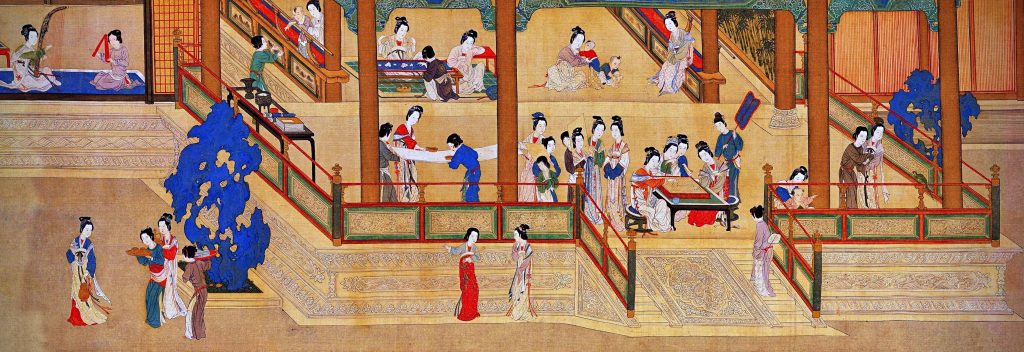

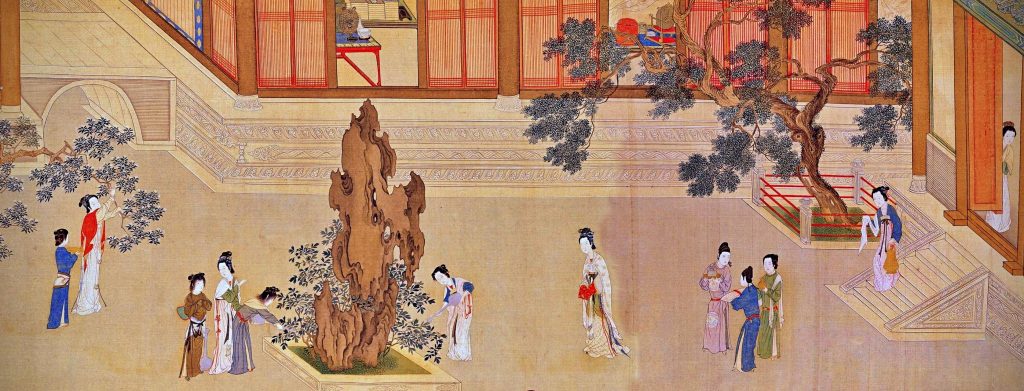

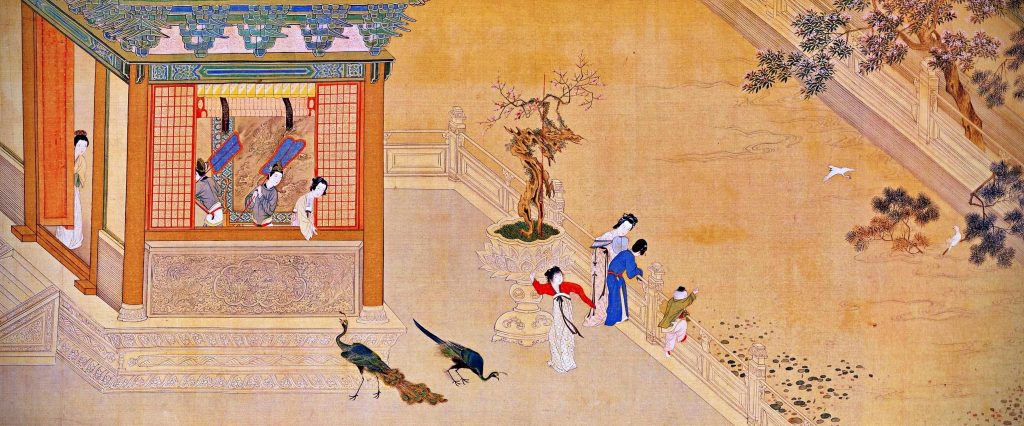

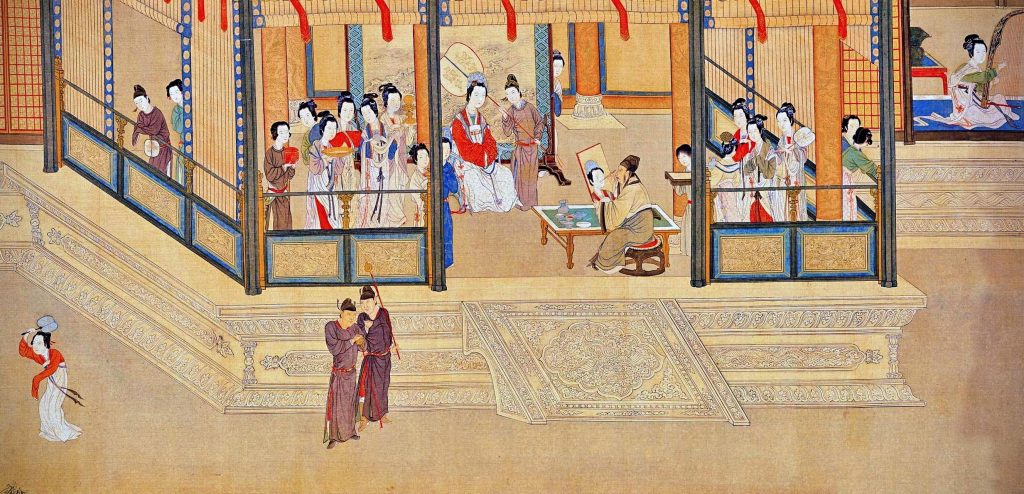

- 9. Spring Dawn at the Han Palace, Qiu Yi

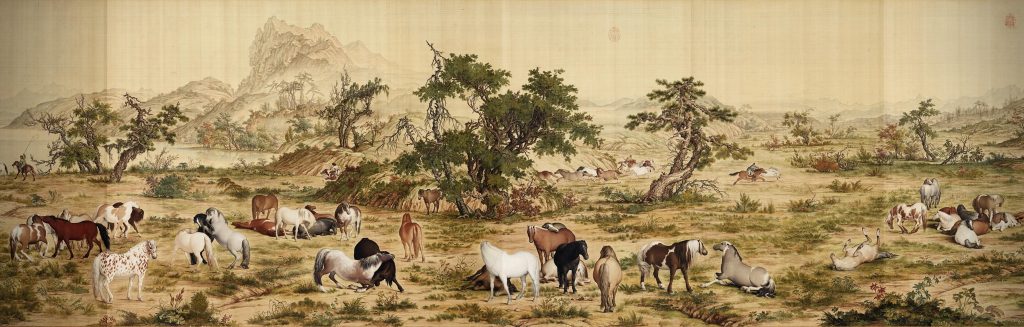

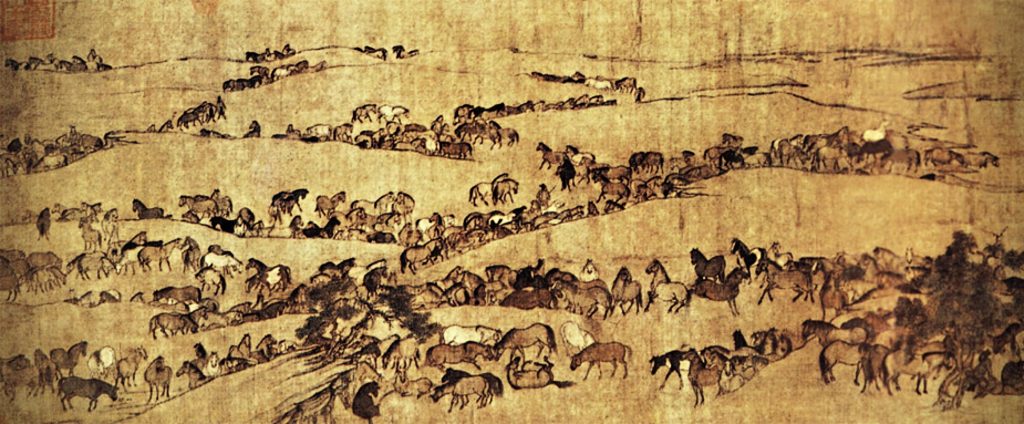

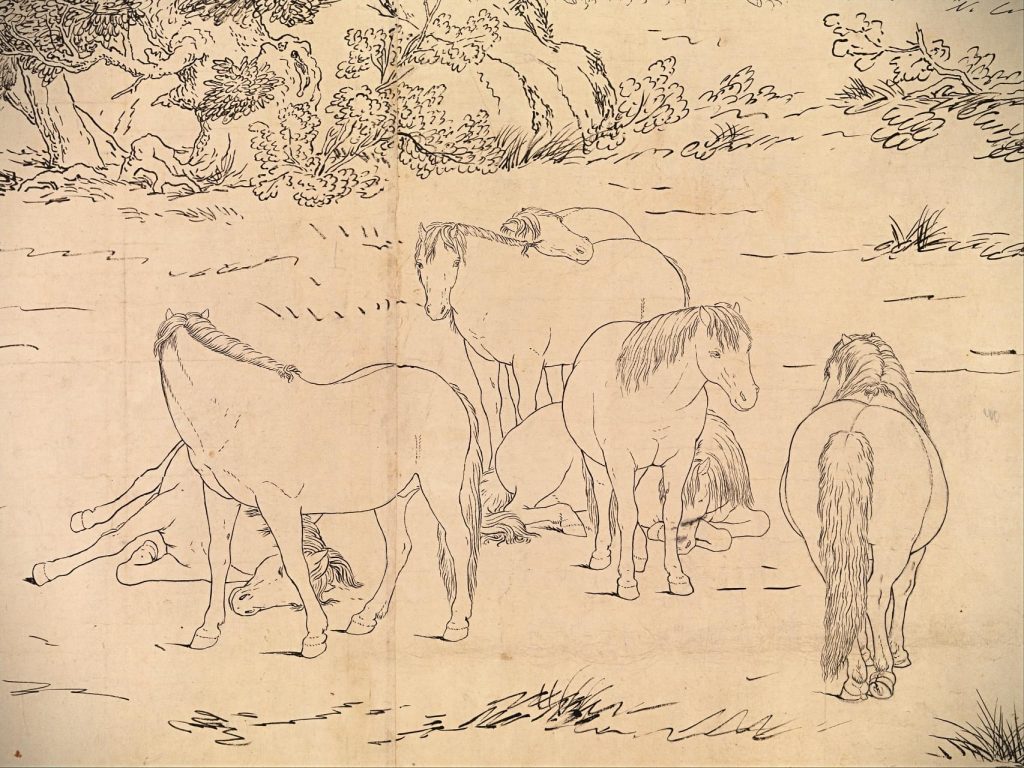

- 10. One Hundred Horses by Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining)

China has a continuous history of thousands of years. China is one of the world's most unique cultures. Over many centuries, Chinese painters have depicted landscapes and animals with great attention to detail. Instead of flat canvases, they created most paintings on hand scrolls. These paintings have touched the hearts of over a billion people.

The Night Revels Of Han Xizai, 10th Century

Discover the 10 most popular Chinese paintings from over 1400 years ago. These handscrolls may also capture your heart.

1. The Nymphs of the Luo River, Gu Kaizhi

Nymph Of The Luo River By Gu Kaizhi

Legend has it that Cao Zhi (1922-232), prince of Cao Wei state, fell in love with the daughter of a magistrate. She married her brother Cao Pi, and the prince was dejected. He composed a poem later about the love of a goddess with a mortal. Gu Kaizhi, a Chinese poet (ca. 344-ca. A Chinese artist (no. 406) was inspired by the story and illustrated the poem.

Unfortunately, recovering the original painting from the 4th century is impossible. Artists made many copies of Nymph of Luo River, most likely during the Song Dynasty. The painting takes the form of a scroll that describes the story in sections. To understand the meaning of all Chinese handcrolls, it is best viewed from left to right. Unfold the scroll to discover this incredible story.

Nymph Of The Luo River By Gu Kaizhi

Cao Zhi, with a group of companions, crosses the Luo River. Gu Kaizhi uses his imagination to the fullest here. He depicts Cao Zhi's meeting with Fu Fei through a clever composition and by using vivid colors. She moves lightly and stops only when she is ready to move. He is shocked when the prince learns that Fu Fei is a nymph. Cao is captivated by Fu Fei's charm and falls in love. In his poem, Cao praises her beauty.

Fu Fei Beauty

Gu Kaizhi (Copy After), The Nymph Of The Luo River, 10-13th Century

From afar, she shines as the sun rises above the rosy mists at dawn. Close up, she is as bright as a lotus that emerges from the ripples of clear water. Cao Zhi Ode to the Nymphs of the Luo River, 222. R.J. Cutter translated the poem.

This poem can be used to inspire you when you want to tell someone how beautiful they look. The nymph is a dignified creature. She sometimes wanders through the water and sometimes flies above the clouds. Fu Fei sings and dances in the air. She and Cao Zhi can see each other. Unfortunately, gods' paths and human paths are different. The love between a mortal and a nymph is short-lived. Fu Fei, accompanied by flying fish and seadragons with long antlers, bids Cao goodbye before disappearing. Cao searches in vain for her. He spends the night unable to sleep, longing for her.

Gu Kaizhi (Copy After), The Nymph Of The Luo River, 10-13th Century

Cao Zhi’s poem is a clear love story. It can be read as an allegory of his failed attempts to gain a regime position. The poem still speaks of the nature of the love and the shortness of life during a period of frequent warfare.

The Luo River Mythical Animals

Nature is a prominent theme in many Chinese traditional paintings. The landscape is merely a backdrop for the various scenes in this handscroll as it tells the story. People and animals are larger than the simplified mountains, trees, and clouds. The painting is a dreamy place, thanks to the birds and dragons that inhabit it. The monster in white pants and a dragon-headed head seems to agree.

Gu Kaizhi (Copy), The Nymph Of The Luo River, 10-13th Century

Gu Kaizhi also depicts water that is smooth, rippling, or swirling. These representations can reflect sadness, excitement, or surprise. The monsters may be running along the river, but it appears that they are flying in the sky. This enhances the atmosphere and makes the painting memorable. We can now see why the Nymphs of the Luo River are a masterpiece.

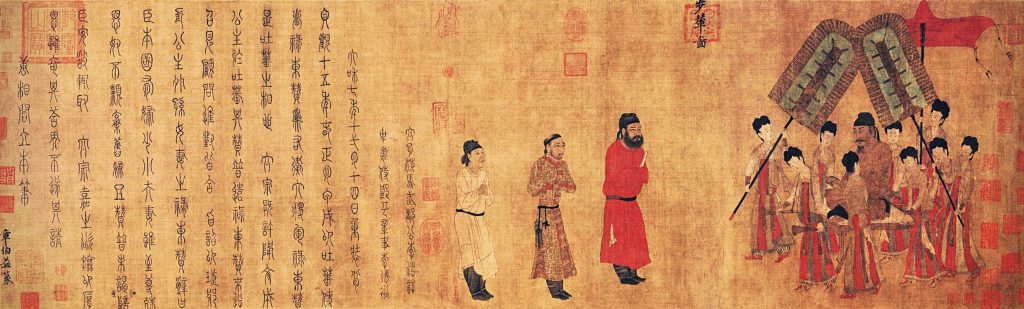

2. Yan Liben, the Tibetan Envoy, is received by Emperor Taizong

Tibet was a fan of the Tang Dynasty in China during the 7th century. On an official visit to China in 634, Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo (ca. 569-ca. In 649), Princess Wencheng fell in love and was pursued by Prince Songtsen Gampo. He sent envoys to China and paid tributes, but they were refused. Gampo's Army marched to China and burned cities until they reached Luoyang, where the Tang Army defeated Tibetans.

Yan Liben (Copy After), Emperor Taizong Receiving The Tibetan Envoy, 14th Century

However, Emperor Taizong (597-849) finally married Gampo Princess Wencheng. Yan Liben (ca. Chinese artist 600-673, Emperor Taizong receiving the Tibetan Envoy, depicted the Tang dynasty's encounter with Tibet. Like many early Chinese paintings from the Song Dynasty (960-1279), this scroll is a copy of the original. The emperor is seated in his sedan in casual clothing.

Yan Liben (Copy After), Emperor Taizong Receiving The Tibetan Envoy, 14th Century

The official of the royal court is in red on the left. In the middle, the terrified Tibetan envoy holds the Emperor in awe. The person on the far left is an Interpreter. The Tibetan minister and Emperor Taizong represent two sides. Their different physical appearances and mannerisms strengthen the dualism in the composition. These differences highlight Taizong’s political superiority.

Yan Liben portrays the scene with vivid colors. He also skillfully draws the characters to give them a lifelike expression. To emphasize their status, he makes the Chinese official and emperor larger than other characters. This famous handscroll is not only rich in history but also shows great artistic ability.

Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo and His Wives

Songtsen Gampo And His Wives, Princess Bhrikuti Of Nepal (Viewer’s Left) And Princess Wencheng Of China (Viewer’s Right).

The painting shows Songtsen Gampo with his wives, Princess Bhrikuti from Nepal (on the viewer's left) and Princess Wencheng from China (on the viewer's right).

In 641, the prime minister of previous Tibet came to Chang'an with the princess to return to Tibet. The princess also brought maps of the Silk Road and promises about trade agreements. She also had a dowry that included fine furniture, silks, and porcelains. The Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo was married to six consorts. Four of them were Tibetan, and two were not. He is credited with being the first person to introduce Buddhism to Tibetans.

3. Zhou Fang - Court Lady Adorning Her Hair with Flowers

Zhou Fang (Attr.), Court Ladies Adorning Their Hair With Flowers, 8th Century, Handscroll, Ink And Colors On Silk, Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang, China. Detail.

China enjoyed a flourishing economy and culture during the Dynasty of Tangs (618-907). During this time, "beautiful woman painting" was very popular. Zhou Fang, who was born into a noble family (ca. Chinese artist Zhou Fang (730-800) created works in this style. His painting, Court Ladies Adorning Their Hair with Flowers, illustrates the ideals and customs of femininity at the time.

Style of Chinese Ladies

A voluptuous figure was the ideal of female beauty in the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Zhou Fang portrayed the Chinese court women with round faces, plump figures, and rounded bodies. The ladies wear long, loose-fitting gowns that are covered with transparent gauze. The dresses have floral or geometric patterns. They stand like fashion models while one is teasing the cute dog.

Zhou Fang, Court Ladies Adorning Their Hair with Flowers (attr. Detail. Court Ladies Adorning their hair with flowers - 8th-century handscroll ink and colors on silk. Liaoning Provincial Museum Shenyang. Detail.

Zhou Fang (Attr.), Court Ladies Adorning Their Hair With Flowers, 8th Century, Handscroll, Ink And Colors On Silk, Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang, China. Detail.

Their eyebrows resemble butterfly wings. Their eyes are slender, their noses full, and their mouths small. The ladies' hairstyles are a high bun with flowers such as lotuses or peonies. They also have fair skin due to the application of white colorants on their skin. Zhou Fang depicts the women as artworks, but this artificiality enhances their sensuality.

The maidservant, holding a fan with a long handle, follows another lady of the palace. The lady in the background appears bigger because she is more important. She stares at the red flower in her hand and is about to use it to decorate her hair. A beautiful crane passes by nearby.

Zhou Fang (Attr.), Court Ladies Adorning Their Hair With Flowers, 8th Century, Handscroll, Ink And Colors On Silk, Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang, China. Detail.

The artist creates analogies by placing non-human images and human figures. The non-human images highlight the delicate beauty of the ladies, who are also a fixture of the imperial gardens. They and the women keep each other company and share their loneliness.

Festival of Flowers

Festival Of Flowers, Butterfly Meeting

Courtiers decorated their hair with silk or paper flowers during the Festival of Flowers. Picnics were held outside to celebrate nature's revival. These ladies were awed by the beauty of these flowers. But they also understood that youth is fleeting.

Zhou Fang excelled not only in depicting the fashion at the time. Through the subtle portrayal of the facial expressions, he revealed the inner emotions of the court ladies. This painting is of great importance in Chinese art because it shows the fashion at the time. The Festival of Flowers, celebrated every March, has become a tradition.

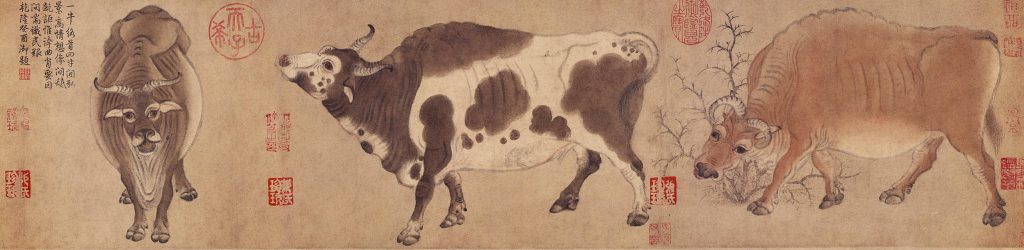

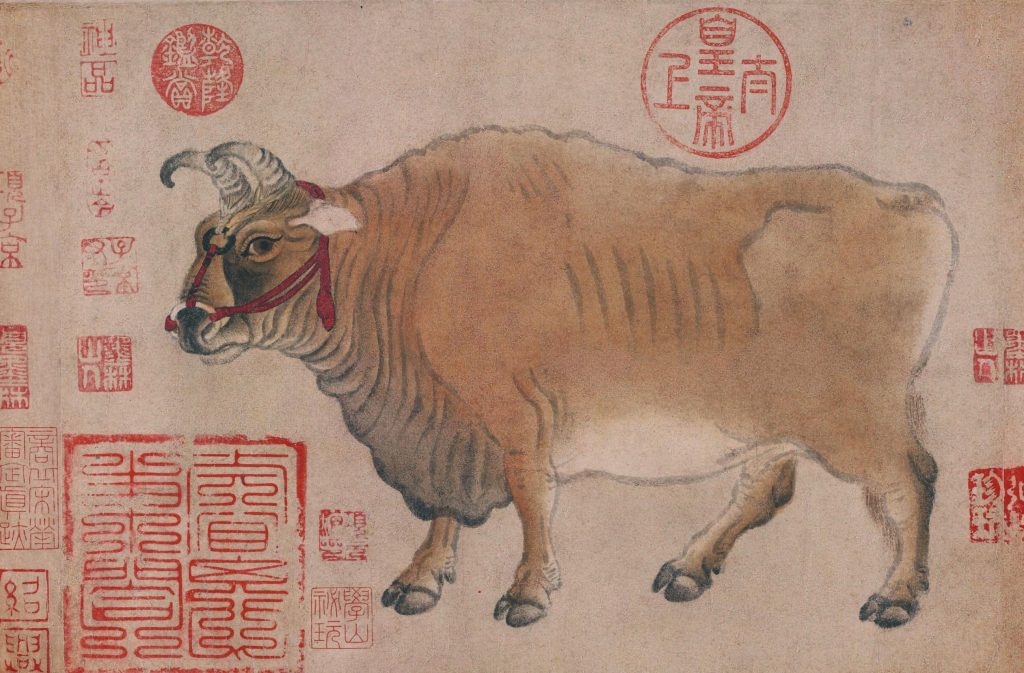

4. Han Huang - Five Oxen

Han Huang (Attr.), Five Oxen, Ink And Color On Paper, 8th Century, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

Han Huang (723-787), chancellor in the Tang Dynasty (618-907), painted five oxen from left to right. They appear to be happy or sad as they stand in a line. Each image can be treated as a separate painting. The oxen, however, form a single whole. Han Huang observed every detail. The oxen's horns and eyes are different, as well as their expressions. Like the five brothers, they are all fascinating characters. Which ox do you prefer?

Han Huang (Attr.), Five Oxen, Ink And Color On Paper, 8th Century

Han Huang is a mystery. We don't know what ox he chose or why he painted Five Oxen. Horse painting was famous during the Tang Dynasty and received imperial patronage. Ox paintings were traditionally thought to be unsuitable for a gentleman’s study.

Han Huang (attr. Five Oxen, ink and color on paper, 8th Century, Palace Museum, Beijing. Stubborn Mo. Detail.

Han Huang (Attr.), Five Oxen, Ink And Color On Paper, 8th Century, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Stubborn Moo. Detail

Han Huang compared himself to the ox on a rein. He could have implied that he liked a quiet life and a relaxed retreat on the mountain when he painted the ox next to the bush. Han Huang, however, was not likely to want to live in seclusion, given his high-ranking position and career. Han Huang could demonstrate his loyalty to the Emperor by painting the ox and rein on it.

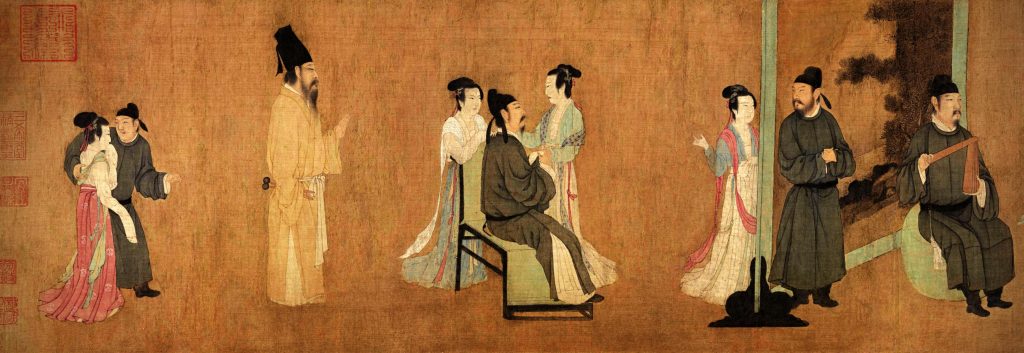

5. The Night Revels Of Han Xizai – Gu Hongzhong

Gu Hongzhong (Attr.), The Night Revels Of Han Xizai, 10th Century, Handscroll, Ink And Colors On Silk, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

Imagine that you're Emperor Li Yu (937-978). Your official servant, Han Xizai, omits morning audiences and talks with you. On top of that, he refuses to be a prime minister. Imagine that you are Emperor Li Yu (ca. What would you say? What would you do? Li Yu took action. Gu Hongzhong (939-975), a court artist, was sent by Li Yu to see what Han Xizai did at home. He painted The Night Revels of Han Xizai to record what Han Xizai did (902-970).

Gu Hongzhong (Attr.), The Night Revels Of Han Xizai, 10th Century, Handscroll, Ink And Colors On Silk, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

Enjoy the Pleasures in Life

Han Xizai had become disillusioned by the regime. He was not willing to serve. Instead, he was enjoying his life. Gu Hongzhong describes the entire scene as a story. The screens act as dividers to divide the painting into sections as the scene unfolds. The painting contains more than 40 figures, each with a different expression and a lifelike appearance.

Gu Hongzhong (attr.), The Night Revels of Han Xizai, 10th century, handscroll, ink and colors on silk, Palace Museum, Beijing, China

In the first scene, we see Han Xizai wearing a futon and a tall, black hat. He is listening to the pipa - a Chinese musical device. The red-clad person is a Chinese scholar. Han Xizai plays a drum in the next scene. He continues to listen to music and entertain himself after a short break. Meanwhile, his guests are talking with the singers.

Gu Hongzhong has cleverly arranged the composition. The scenes are independent, but the composition remains unified. In one scene, the artist uses a candlestick to indicate the time. This painting appears to be about personal life at first glance. It also gives a hint at the customs and culture of that time.

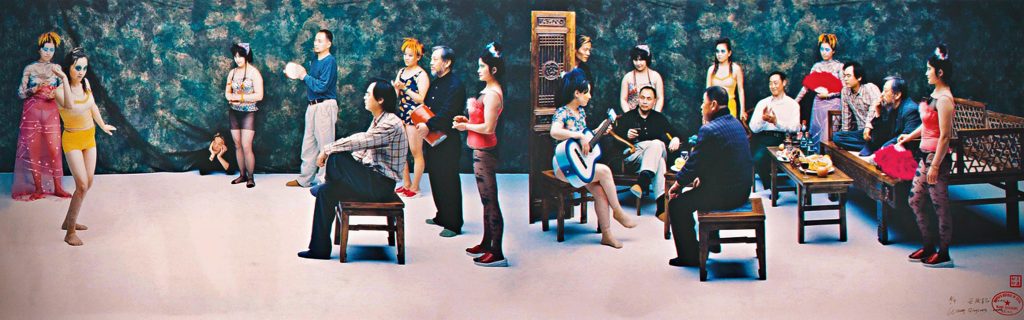

The Night Revels Of Lao Li

Wang Qingsong, The Night Revels Of Lao Li, 2000, Chromogenic Print, Private Collection

Wang Qingsong is a conceptual artist who created The Night Revels of Lao Li in 2000 based on Gu's work. In his photo, he dresses his characters in modern clothes to comment on the current Chinese culture. The men in his guests' company are dressed in simple casual slacks, dark shirts, and house slippers. Wang Qingsong, here, is not a spy of the imperial court or state. He became a cultural spy and appeared as an outsider in this strange, artificial universe.

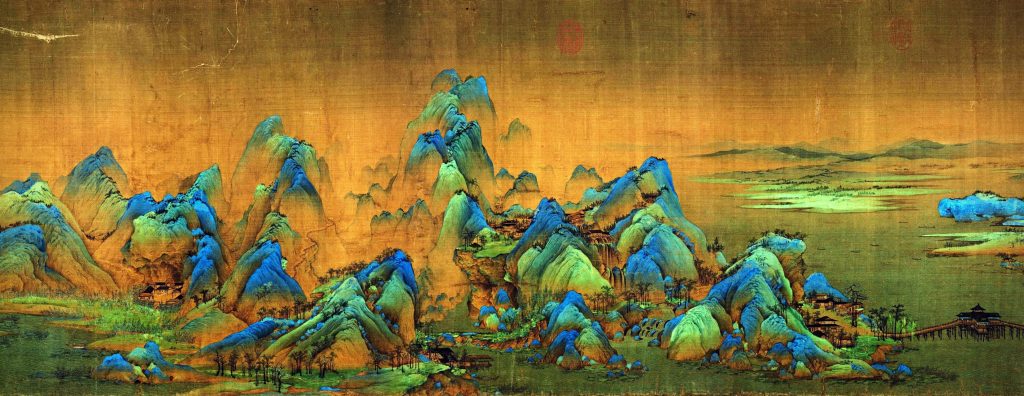

6. Wang Ximeng - A Thousand Li of Mountains and Rivers

Wang Xi Meng, A Thousand Li Of Rivers And Mountains, 1113, Handscroll, Ink And Colors On Silk, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

Nature was also a favorite subject for officials and scholars. Wang Ximeng (2010-1119) was one such painter. He was a prodigious talent from a young age, mentored by Emperor Huizong. At the tender age of 17, in 1113, Wang Ximeng crafted the artwork "A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains."

Wang Xi Meng, A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, 1113, handscroll, ink and colors on silk, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

Tragically, he passed away just a few years later, but not before leaving behind one of the most magnificent and expansive pieces in the annals of Chinese art. This artwork stretches nearly twelve meters.

The painting stands as a testament to artistic brilliance. Shades of azurite and malachite dominate, complemented by hints of muted brown. Wang Ximeng employs varied vantage points to depict a sprawling landscape, beautifully capturing verdant hills and architectural marvels. This artwork's sheer magnitude, vivid hues, and intricate nuances are awe-inspiring. A closer look reveals serpentine trails leading to secluded enclaves.

Wang Xi Meng, A Thousand Li Of Rivers And Mountains, 1113, Handscroll, Ink And Colors On Silk, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

The artist's meticulous brushwork and flawless technique express his deep admiration for the magnificence of nature. In his painting, mountain formations rise and fall against a clear sky. Wang Ximeng has opened up a new world of landscapes you'll never tire of exploring.

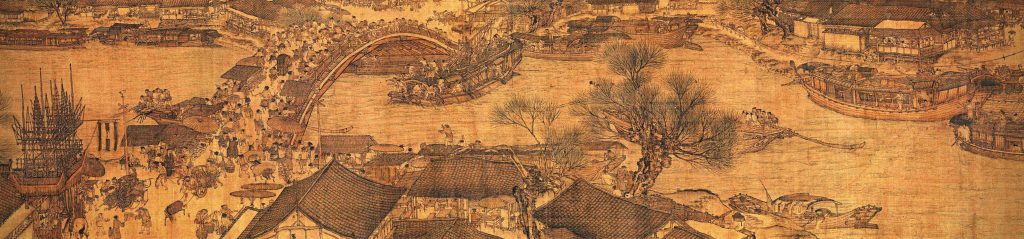

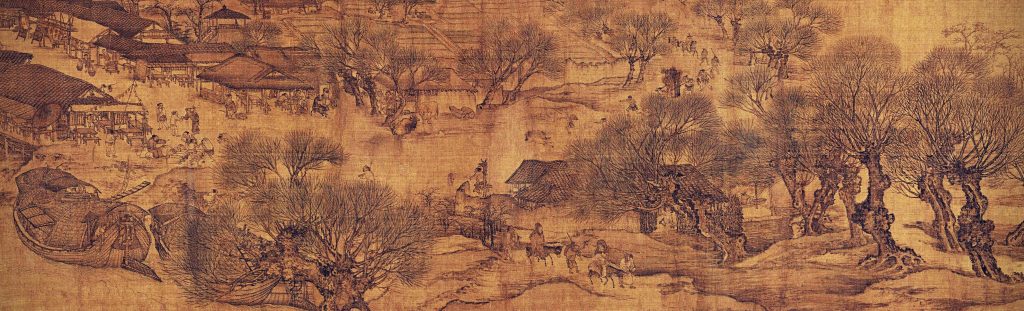

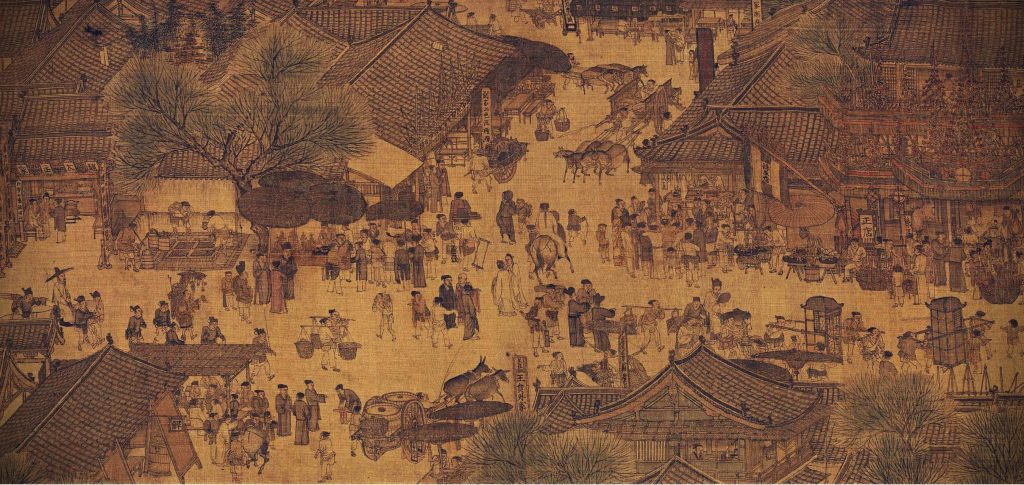

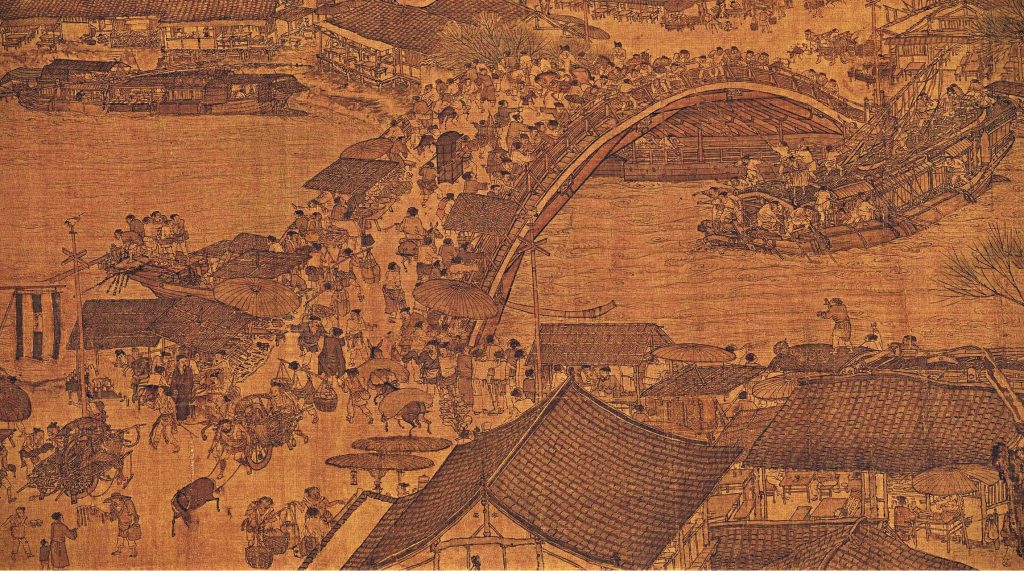

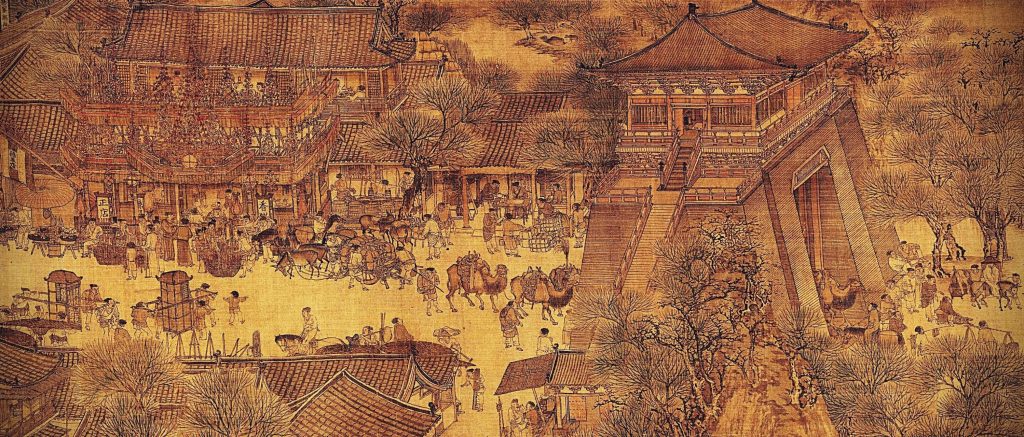

7. Zhang Zeduan, Along the River during the Qingming Festival

Zhang Zeduan, Along The River During The Qingming Festival, 12th Century, Handscroll, Ink And Colors On Silk, Palace Museum, Beijing, China

Another artist, Zhang Zeduan (1085-1145), also painted the landscape with his work Along the River During the Qingming Festival. Instead of focusing on the vastness and beauty of nature, he chose to capture the everyday life of people in Bianjing (modern-day Kaifeng).

His work tells us a lot about Chinese people's life in the 11th and 12th centuries. It shows, for example, a river ship lowering the bipod mast of its mast before it passes under the prominent bridge in the painting. The multitude of people interfacing with each other reveals the subtleties of the class structures during the festive days.

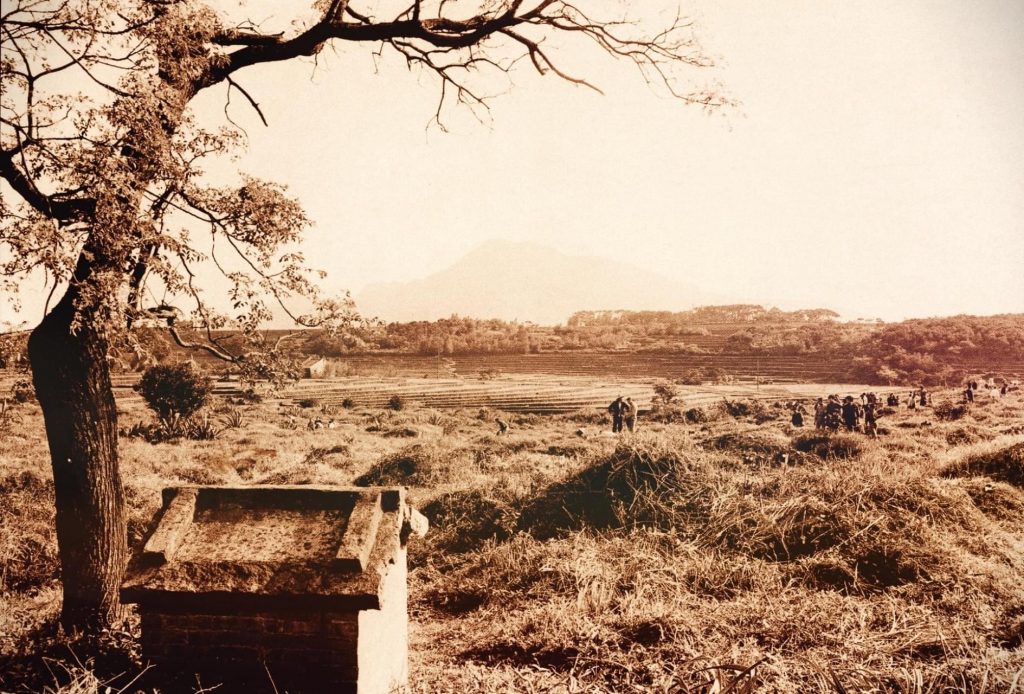

Qingming Festival

Since over 2500, the Chinese have celebrated the Qingming Festival. Chinese families clean graves during this festival that takes place every year between April 4th and 6th. The Chinese also make offerings and pray to their ancestors. The offerings include food and incense.

The Qingming Festival is held in the Tamsui District of New Taipei. 1970. Photo by Cai Kunghuang, via Wikimedia Commons. (CC BY 3.0).

This painting does not depict the ceremonial aspect of the Qingming Festival but rather the festive spirit. Zhang Zeduan depicts all social classes, from the rich to the poor. He gives glimpses into period clothing and architecture. The painting is also considered one of the most famous Chinese paintings. It was even called "China’s Mona Lisa."

Zhang Zeduan, Along The River During The Qingming Festival, 12th Century, Handscroll, Ink And Colors On Silk, Palace Museum, Beijing, China

Zhang Zeduan has managed to fit 814 people in this five-meter scroll. He also included 60 animals, 30 vehicles, 20 buildings, 8 sedan chairs, and 170 trees. The painting is divided into two sections: the rural area and the densely populated city.

The right section has crop fields and farmers. On the left is the densely populated city. On the left side, in the urban area, there are people from all walks of life. Some people are loading cargo on a boat while others are begging, and monks ask for alms.

Zhang Zeduan, Along The River During The Qingming Festival, 12th Century, Handscroll, Ink And Colors On Silk, Palace Museum, Beijing, China

Rainbow Bridge

The focus of the scroll is the place where the bridge crosses the river. The Rainbow Bridge is lined with vendors. The crowds of people are a constant source of activity. As the boat approaches the bridge at an awkward angle, its mast is not fully lowered. The crowds are gesturing at the boat from the bridge and the riverside.

Zhang Zeduan, Along the River During the Qingming Festival, 12th century, handscroll, ink and colors on silk, Palace Museum, Beijing, China.

This painting, which depicts life during the Song Dynasty from 960 to 1279, has been copied, imitated, and forged numerous times. According to legend, Qiu Ying was a 16th-century artist who painted beautiful replicas of Along the River During the Qingming Festival. This prompted forgers of his works.

Enlightened Era

The Qing copy may have been so prized that the Qianlong emperor composed this poem:

It is a truly amazing scene with an opportunity to discover vestiges from the past. The size of Yu was a marvel at that time. Now, we mourn the fates of Hui and Qin. The poem appears on the copy painting of Qianlong, Emperor, 1742.

Zhang Zeduan, Along the River During the Qingming Festival, 12th century, handscroll, ink and colors on silk, Palace Museum, Beijing, China.

Certain people think the picture was painted as a message from the artist to the Emperor to detect dangerous trends under the surface of prosperity. Observe that the guards at the city gates and docks seemed unalert. The name of the painting may refer to an era of light and brightness instead of a festival.

The River of Wisdom

Along The River During The Qingming Festival, Expo, Shanghai, China, 2010

The River of Wisdom was created as a 3D animated digital version of this painting. The scroll is approximately 30 times larger than the original. The computer-animated wall has animated characters and objects that portray the scene with four-minute day and night cycles. The animation is currently on permanent display at the China Art Museum in Shanghai.

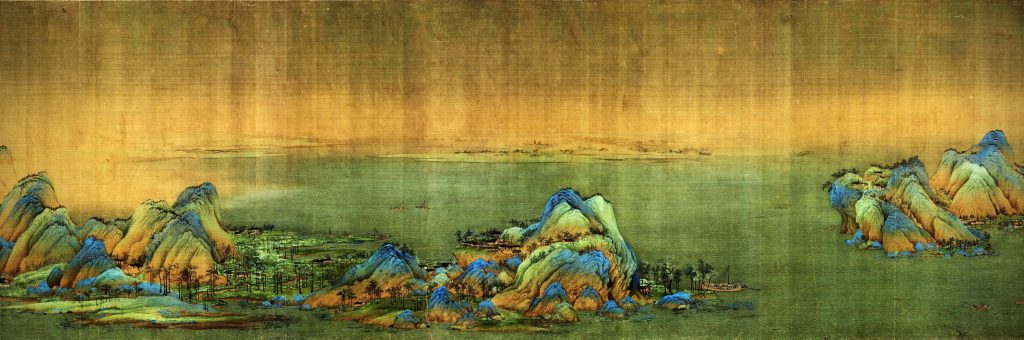

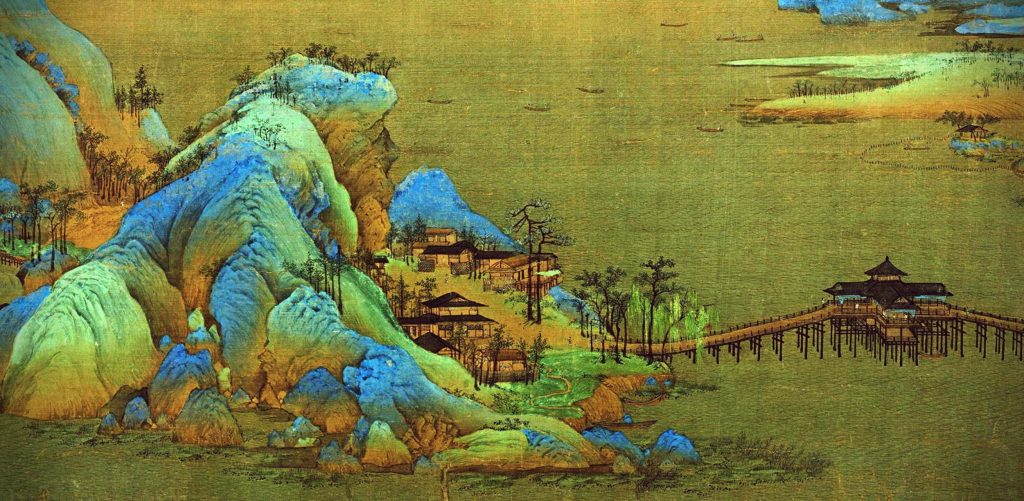

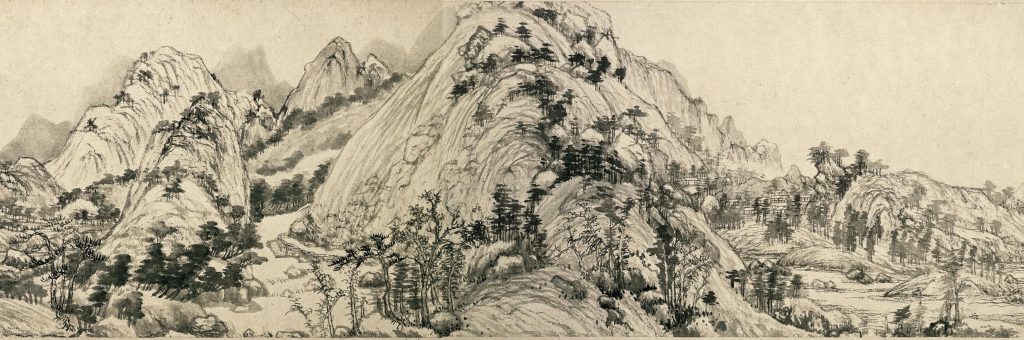

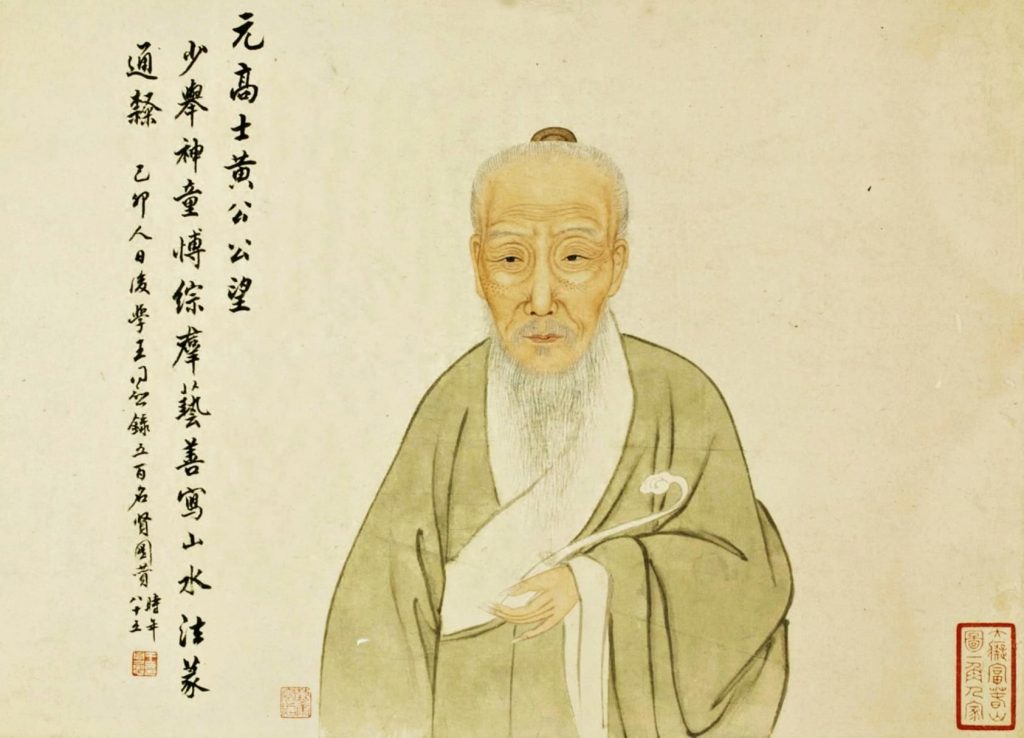

8. Huang Gongwang: Dwelling in Fuchun Mountains

Huang Gongwang, Dwelling In The Fuchun Mountains, The Master Wuyong Scroll, C. 1350, Ink On Paper, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

Huang Gongwang (1269-1354), who was 10 years old at the time, had just witnessed the fall of the Song Dynasty to the Yuan Dynasty. Many painters were openly against official art tendencies. They didn't want to work and live at the Mongolian Court. These artists re-used themes from the Song Dynasty in their paintings.

Huang Gongwang, like many intellectuals at the time of his career development, found it difficult to achieve a successful career. He worked as a legal assistant for several years. He was briefly jailed for tax violations. He then turned to Taoism, completely disillusioned. His many nicknames reflected this: Silly Taoist priest, Lonely Mountain Peak, and Abode Of Purity.

Huang Gongwang, Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, The Remaining Mountain, Artist’s self-portrait, c. 1350, handscroll, ink on paper, Zhejiang Provincial Museum, Hangzhou, China.

He taught philosophy in the Fuchun Mountains near Hangzhou during his final years. Huang Gongwang only began painting seriously at age 50. In 1350, he finished one of his most famous paintings, Dwelling in Fuchun Mountains. It's a manifesto for the secluded lifestyle.

The Remaining Mountain

Huang Gongwang, Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, The Remaining Mountain, c. 1350, handscroll, ink on paper, Zhejiang Provincial Museum, Hangzhou, China

At first, Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains was only available on one scroll. Wu Hongyu was one of the original owners in 1650. He loved the painting so much that he burned it shortly before death. He thought that he would be able to take it with him into the afterlife. Wu Hongyu’s nephew saved the artwork from total destruction. The painting, however, was already on fire and had been torn in two. The smaller piece was renamed The Remaining Mountain. The Zhejiang Provincial Museum, Hangzhou, now houses the smaller piece. The Master Wuyong Scroll, the longer piece, is now in the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

The scroll shows early autumn along the Fuchun River. The image sweeps along the horizon, revealing a vast, majestic landscape. The mountain peaks reach the sky, while deep canyons are visible in between. The pines are proudly standing, and the forest in the distance is hidden by a haze.

The trees may be uneven, dense, or rare. Human figures, country houses, bridges, and boats are all lost in the landscape. The vaguely visible tops of the trees on the mountain give the painting a feeling of tranquility and rhythm.

Master Wuyong

Huang Gongwang, Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains, The Master Wuyong Scroll, c. 1350, ink on paper, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

The artist carried the scroll when he traveled, sketching the composition in one session. The artist went back to it whenever he felt like it, but he never finished it. Huang Gongwang uses very dry brushstrokes and light ink washes for his paintings. This allowed him to create a dynamically complex mass.

The looseness of his drawing lends the scene a somewhat unkempt appearance. It also draws our attention away from the carefully calculated scroll construction. In their more structured approach to painting, subsequent imitators lost the spontaneity of this style.

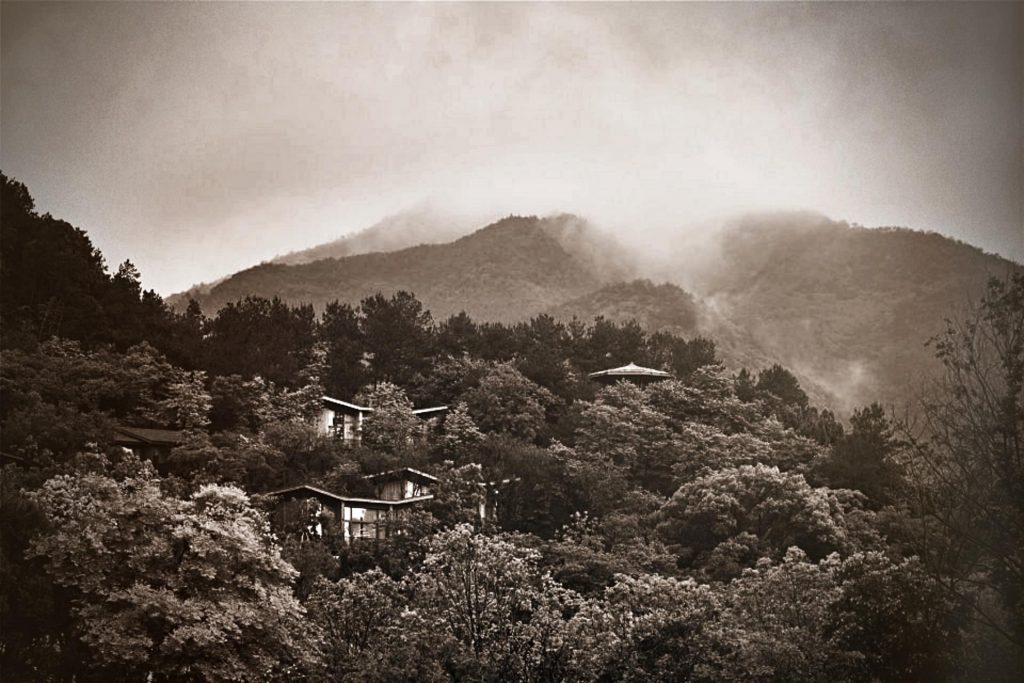

The Fuchun Resort

Fuchun resort with guest rooms hiding in the mountain

Fuchun Resort with hidden rooms in the mountains. The painting reveals the harmony between man, nature, and the artist. Huang Gongwang cultivated himself as a painter in his old age. He showed us Southern China's beauty with its hills and rivers. Fuchun Resort, a collection of guesthouses that combine Chinese cultural elements and Western design, is located in this area.

9. Spring Dawn at the Han Palace, Qiu Yi

Qiu Ying, Spring Dawn In The Han Palace, 1552, Handscroll, Color On Silk, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

Qiu Ying (ca. 1494 - ca. 1552 (pronounced Ch'iu Yiing) was the son of a Taicang peasant. He became an apprentice of a lacquer artist in Suzhou after moving there. He was a talented painter despite his humble family origins. He painted in the gong bi technique, a meticulous realist style in Chinese painting. The brushstrokes are very precise and outline the details. It's often very colorful and depicts figures or narratives.

Qiu Ying, Spring Dawn in the Han Palace, 1552, handscroll, color on silk, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. Detail.

Enjoy the Palace

Qiu Ying, Spring Dawn In The Han Palace, 1552, Handscroll, Color On Silk, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. Detail.

The artist portrayed court ladies in his paintings and was inspired by history. In Spring Dawn in Han Palace, he imagines court ladies from the Han Dynasty palace (206 BCE-220 CE). The handscroll begins with the gates of the palace and leads us to sumptuous courts. Elegant ladies are seen here engaging in leisure activities.

One lady is leaning on the rails to watch the fish swimming in the lake with her children. Two peacocks wait impatiently for food as a woman throws food at them.

Qiu Ying, Spring Dawn In The Han Palace, 1552, Handscroll, Color On Silk, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. Detail.

QiuYing had a talent for describing the structure and furniture of buildings. He also accurately represented architectural features. He modeled ladies' dresses after those from the Tang and Song Dynasties. Their bodies are slimmer and more delicate. This image of female beauty was recognized during the Ming Dynasty (1365-1644).

In another scene, the ladies of the court play weiqi, or Go, an ancient Chinese board game. On the left, one woman prepares a roll of woven silk while another weaves a tapestry. A mother is also seen playing with her children.

Mao Yanshou & His Deception

These images portray a harmonious court life. Court life had its more competitive aspects. Qiu Yi painted a narrative of the concubines to Emperor Yuan (75 BC - 33 BC). In ancient times, an emperor would be presented with portraits before meeting the women. So he would know who to pick as his consort.

In order to catch the attention of the emperor, court ladies would often pay court artist Mao Yanshou a bribe to make them look more beautiful than they were. Wang Zhaojun, however, refused to pay the artist. Mao Yanshou, as revenge, painted her with moles all over her face.

Qiu Ying, Spring Dawn In The Han Palace, 1552, Handscroll, Color On Silk, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. Detail.

Wang Zhaojun is seated in front of the screen as the artist paints the portrait. As they watch the progress of the painting, other concubines gossip among themselves. In the foreground, two eunuchs are chatting. They know about the bribes and Mao Yanshou’s deception.

After seeing Mao Yanshou’s distorted picture, Emperor Yuan did not visit Wang Zhaojun. She remained a woman-in-waiting. One day, however, the ruler from the Xiongnu Empire came to the Han Court to establish a marriage relationship.

Wang Zhaojun was chosen as the bride by the emperor, who thought she was not the most attractive of all his ladies. Emperor Yuan only realized she was the prettiest woman in court when summoned. The offer was already made, but it was too late. The emperor was furious at Mao Yanshou for his deception and ordered that the artist be executed.

10. One Hundred Horses by Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining)

Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining), One Hundred Horses, 1728, Ink And Colors On Silk, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. Detail.

Giuseppe Castiglione is also known for his One Hundred Horses. A European painter, Castiglione (1688-1766) adapted his style to Chinese aesthetics. He served as a court artist for three Chinese emperors.

The artist was raised in Milan, where he studied painting under the tutelage of a master. He joined the Society of Jesus at age 19 in Genoa. He was a Jesuit but never ordained a priest. Instead, he joined as a brother.

Castiglione first arrived in Macau and then Beijing, where he stayed with a Jesuit Church. One day, Emperor Kangxi (1654-6722) came across one of his paintings. The artist was then assigned some disciples. Castiglione was known in China as Lang Shining.

He was an artist to three emperors, Kangxi Yongzheng and Qianlong. He adapted Western styles to Chinese themes and tastes. Chinese portraiture, for example, was not able to use strong shadows in chiaroscuro. Emperor Qianlong believed that shadows looked dirty. Castiglione, who painted the portrait of Qianlong, reduced light intensity to ensure the face was free from shadows.

Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining), Qianlong In His Studies, 18th Century. Wikimedia Commons.

Castiglione created his One Hundred Horses as a Chinese handcroll measuring nearly eight meters long. He painted the horse largely in a European style. Nevertheless, Castiglione also reduced the dramatic chiaroscuro shade. Only traces of shadow are visible under the horses' hooves. Some of the horses appear to be in a pose called "flying gallop," which was not common in European paintings.

Imperial Horses

Li Gonglin, Imperial Horses At Pasture After Wei Yan, Ca. 1085, Handscroll, Color On Silk, Palace Museum, Beijing, China. Detail.

In the Chinese culture, the horse was a very important animal. Therefore, it has a special place within Chinese art. Castiglione was inspired by the Chinese painter Li Gonglin (1049) to create this piece. Some horses are dispersed into groups. Some graze on the meadow while others chase each other and roll on the ground. The horses have been vividly drawn, creating a lively and idyllic scene.

Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining), One Hundred Horses, 1723–25, Metropolitan Museum Of Art, New York, Ny, Usa. Detail.

Castiglione painted most of his works in tempera and silk. He had to adapt to the Chinese way of working. Painting on silk is not a retouchable medium. Castiglione first worked out all the details on paper before transferring them to silk.

Castiglione shows horses playing together or swaying in the grass, similar to Li Gonglin’s painting. Figures are usually shown in a foreshortened form. The artist, who paints trees in the Chinese tradition, uses shading. The contrast between lightness and darkness is reduced.

Crossing the River

Three horses have crossed the river, and others are following behind. Some horses quench their thirst near the river. Some horses are frolicking and playing with their offspring while others rest quietly. In Chinese art, horses are symbols of speed, endurance, and victory. Likewise, certain trees represent different concepts. The oak, for example, is a sign of masculine power.

Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining), One Hundred Horses, 1728, Ink And Colors On Silk, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. Detail.

The willow tree is a Buddhist sign of humility. The pine tree represents longevity and resilience. The red maple leaves are a good way to describe the fall season.

Palace art from the Qing Dynasty showed early traces of European influences. Castiglione used light and shadow to create a new style that combines Western techniques with Qing aesthetics. Castiglione became famous for his depictions of horses.

Live Like Horses

We will live as horses. Let go of your old iron fences. There are many ways to regain our senses. Break down the stalls, and we'll be able to live like horses.

One Hundred Horses

The National Palace Museum has created a video of One Hundred Horses.

Giuseppe Castiglione, One Hundred Horses. National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

The River of Wisdom

Scroll Along the River during the Qingming Festival to see an animated version of the River of Wisdom Fung p.y.

No Comments Yet...