Art Periods: Journey Through Art History

- Curious about the beginnings of art?

- A Comprehensive Look at Different Art Periods

- A Comprehensive Art Movement Timeline

- The Byzantine Period (330 – 1453): Eastern Roman Empire and the Spread of Christianity

- The Romanesque Period (1000 – 1300): Conveying Knowledge Through Artistic Expression

- The Gothic Period (1100 – 1500): Unity of Liberty and Apprehension

- The Renaissance Period (1420 – 1520): Humanism Reborn

- Mannerism (1520 – 1600): A Glimpse into the Emerging Aesthetic of Kitsch

- Glorious Baroque Period (1590 – 1760)

- Beyond Baroque: The Rococo Art Period (1725 – 1780)

- Return to Classical Principles: Classicism (1770 – 1840)

- Romanticism (1790 – 1850): Infusing Art with Profound Emotion

- Realism Period (1850 – 1925): The Age of Objectivity

- Impressionism (1850 – 1895): The Dawn of Modern Art

- Symbolism Period (1886 – 1900): Meaning in Art

- Embracing Expression Beyond Naturalism: Post-Impressionism Period (1886 – 1905)

- Art Nouveau (1890 – 1910): Klimt's Shining Epoch

- Expressionism Period (1890 – 1914): Art as Political Commentary

- Cubism (1906 – 1914): The Art of Distorted Realities

- Futurism Period (1909 – 1945): The Anarchic Wave in Art

- Dadaism (1912 – 1920): Nonsense as a Revolutionary Artistic Language

- Constructivism (1913 – 1930): Bridging Cubist Forms with Futurist Dynamics

- The Harlem Renaissance (1920 – 1930): A Renewal of African-American Artistic Expression

- Surrealism (1920 – 1930): Reality Defied

- New Objectivity (1925 – 1965): The Precision and Coldness of Art

- Art's Evolution Beyond European Boundaries: Abstract Expressionism (1948 – 1962)

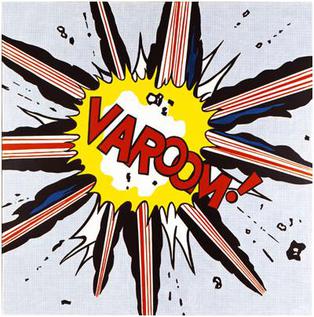

- Pop Art (1955 – 1969): Where Everything Becomes Art

- Neo-Expressionism (1980 – 1989): A Contemporary Echo of Fauvist Spirit

Art is a timeless language that humans have spoken throughout history, painting stories and emotions on the canvas of our existence. Exploring different art periods is like leafing through the pages of our collective diary, revealing the vibrant hues of our cultural evolution. Understanding these periods allows us to appreciate the unique brushstrokes that shaped our past, fostering a deeper connection to the beauty and diversity of our shared human journey.

Curious about the beginnings of art?

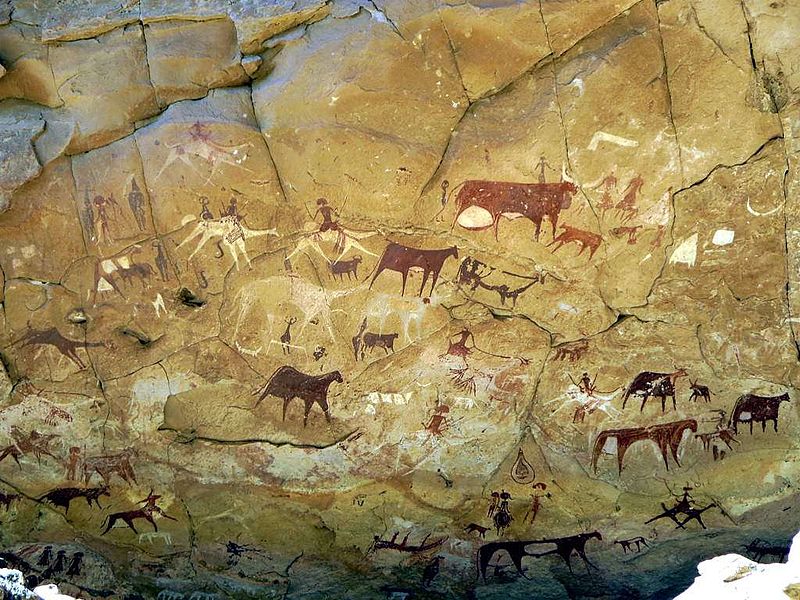

The dawn of artistry is marked by Paleolithic cave paintings, dating back approximately 40,000 years. Captivating rock shelter paintings and drawings reveal insights into early human activities and cultures. While the purposes of these ancient artworks remain unclear, scholars suggest they served as tools for recording cultures, experiences, and local narratives, passed down through generations.

Prehistoric Rock Paintings At Manda Guéli Cave In The Ennedi Mountains

Despite the richness of early artistic expressions, the official art history timeline, recognized during the Romanesque era, omits Stone Age cave paintings and ancient frescos from Egypt and Crete around 2000 BCE. This omission is attributed to the limited geographical scope of these early artworks, which contrast with the broader origins of officially recognized art eras, primarily in Europe and parts of North and South America. The unacknowledged artistic brilliance of early human expression prompts intriguing questions about their realistic depictions, inspirations, and the transmission of artistic practices in prehistoric civilizations. This article aims to unveil the ever-changing artistic styles of the human creative mind, providing insights into the complexities of different art periods.

A Comprehensive Look at Different Art Periods

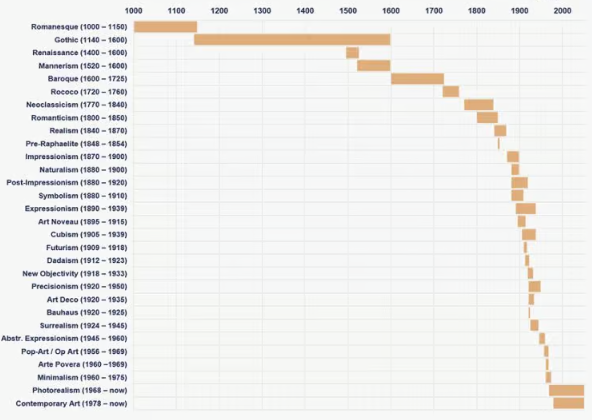

Exploring the diverse tapestry of human history, precisely delineating distinct art periods proves an intricate challenge. The dates provided below serve as approximate markers, considering the fluid progression of each artistic movement across multiple countries. Art periods often intertwine, showcasing substantial overlaps, and some endure for millennia, while others unfold in less than a decade. Art, a continual journey of exploration, witnesses the emergence of contemporary periods organically from their predecessors.

The remnants of ancient Greece, manifested in its temples, ruins, and archaeological marvels, offer a profound glimpse into the classical styles that have profoundly influenced Western art for centuries. The termination of our chronological account merely 30 years ago may appear peculiar, underscoring the inadequacy of the traditional art era concept to encapsulate the diverse styles that have blossomed since the beginning of the 21st century.

In an era characterized by rapid living and digital expanses, some art historians contemplate the demise of the traditional concept of painting. However, it would be imprudent to dismiss the relevance of traditional mediums in the 21st century. The medium of art endures as a timeless conduit for sharing unique human experiences, mirroring the ancient practice of cave paintings that transcends contemporary classification systems.

A Comprehensive Art Movement Timeline

Now, let's take a closer look at the social, cultural, and historical backgrounds that define each of the different art eras we discussed earlier. You'll notice how each era is influenced by those that came before. Just like human thoughts and feelings, art keeps changing and growing. Also, keep in mind that this art timeline mainly covers the history of Western and mostly European art.

The Byzantine Period (330 – 1453): Eastern Roman Empire and the Spread of Christianity

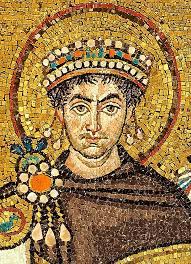

The art of the Byzantine Epoch, spanning from 330 to 1453, reflects the cultural and religious dynamics of the Eastern Roman Empire. Infused with the influence of Christianity, Byzantine art became a powerful vehicle for expressing religious devotion and imperial authority. Iconic mosaics, intricate frescoes, and ornate religious artifacts characterize this period, showcasing a distinctive blend of classical and Christian themes. The art of the Byzantine era serves as a visual testimony to the enduring legacy of the Eastern Roman Empire and its profound impact on the propagation of Christianity across the medieval world.

One prominent form of Byzantine painting is the icon, a sacred image believed to have a direct connection to the divine. Icons were venerated as objects of religious significance, fostering a deep sense of spirituality among the Byzantine populace. Mosaics were another prevalent artistic expression, adorning the interiors of churches and palaces.

The center of the Byzantine Empire was Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), which served as the capital and political, cultural, and economic hub of the Eastern Roman Empire throughout much of its existence.

The Romanesque Period (1000 – 1300): Conveying Knowledge Through Artistic Expression

Frontal Altar From Avia Around 1200

The Romanesque Period was an important era in European art and architecture. Characterized by a revival of interest in the classical heritage of the Roman Empire, this era witnessed the construction of grand cathedrals, monasteries, and castles. Architectural features such as rounded arches, thick walls, and sturdy pillars were prominent, reflecting both practical considerations and a desire to emulate Roman architectural elements.

In terms of art, Romanesque visual expression was primarily manifested in illuminated manuscripts, sculpture, and mural paintings. Manuscript illumination, characterized by intricate illustrations in religious texts, showcased vibrant colors and intricate details. Sculptures adorned cathedrals, portraying biblical figures, saints, and scenes from Christian teachings. The interior walls of churches were often adorned with mural paintings, depicting religious narratives in a visually compelling manner.

The art of the Romanesque Period served not only as a religious expression but also as a means of communicating biblical stories and teachings to a largely illiterate population. The monumental architecture and artistic endeavors of this era laid the groundwork for the transition to the more refined and expansive Gothic style that followed in the later medieval period.

In Romanesque paintings, mythological creatures such as dragons and angels are frequently depicted, and these artworks are predominantly housed within churches. Essentially, paintings from the Romanesque period served the primary function of disseminating biblical stories and promoting Christianity. The nomenclature of this artistic era is derived from the prevalent use of round arches reminiscent of Roman architecture, notably present in contemporary church structures.

The Gothic Period (1100 – 1500): Unity of Liberty and Apprehension

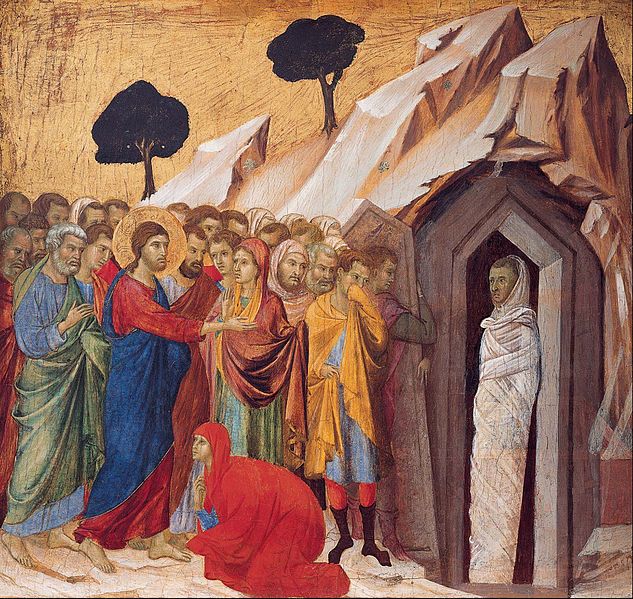

"The Raising Of Lazarus" (1310–1311) By Duccio Di Buoninsegna

The Gothic Period, a transformative period emerging from the Romanesque legacy in France, is renowned for encapsulating the intricate tapestry of contrasting emotions that defined its time. As individuals reveled in newfound freedoms of thought, there was a simultaneous grappling with the pervasive fear of an impending apocalypse. This complex dichotomy found vibrant expression in Gothic art, where the diversity of subjects became a visual narrative, reflecting the nuanced sentiments that permeated society.

While Christianity remained a central focal point, the era witnessed an intellectual blossoming that prompted Gothic paintings to explore a broader array of themes. The shift was notable, moving away from depictions of divine entities to scenes portraying the multifaceted human experience. Laborers toiling in fields and hunting scenes became prevalent, marking a departure from the more ethereal subjects of the preceding Romanesque period.

The increased attention to human figures in Gothic art was a distinctive feature, with artists skillfully rendering more lifelike and individualistic faces. This shift in portraiture can be attributed in part to advancements in three-dimensional perspectives, allowing for a more nuanced representation of the human form.

The expansive interiors of Gothic churches provided a conducive canvas for this evolution, symbolizing a broader intellectual and artistic horizon. The flourishing artistic freedom coincided with a pervasive fear of an impending apocalypse, leading to a decline in faith that prompted art to extend beyond ecclesiastical confines. Artists like Hieronymus von Bosch and Breughel pushed the boundaries, creating works deemed unsuitable for traditional church settings.

In stark contrast to the Romanesque period, where individual artists were often overshadowed by the overarching message, Gothic art witnessed a renaissance of recognized creators. Visionaries like Giotto di Bondone emerged, contributing significantly to the establishment of distinct art schools across Europe. The Gothic era, with its intricate tapestry of freedom and fear, not only transformed artistic expression but also heralded a profound shift towards a more individualized and diverse artistic landscape that laid the groundwork for the Renaissance period that would follow.

One fascinating fact about the Gothic period is the development of the pointed arch, a key architectural feature. Unlike the rounded arches of the Romanesque era, the pointed arch distributed weight more efficiently, allowing for taller and more spacious structures. This innovation contributed to the construction of towering cathedrals and churches, showcasing the Gothic commitment to height and verticality in architecture. Additionally, the period saw a surge in the use of stained glass windows, transforming cathedrals into luminous showcases of biblical stories and religious narratives.

The Renaissance Period (1420 – 1520): Humanism Reborn

"David" By Michelangelo (1501–1504)

The Renaissance period stands as one of the most renowned epochs, showcasing luminaries like Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. Rooted in a profound admiration for the individual human experience, this era drew inspiration from the artistic and philosophical legacies of ancient Romans and Greeks, embodying a cultural rebirth that manifested across various art movements in Europe.

Sandro Botticelli, a prominent early Renaissance painter, gained renewed acclaim during the pre-Raphaelite movement. Sculpture in the Early Renaissance reached new heights under the influence of artists like Donatello, who, inspired by Classical traditions, earned recognition as one of Florence's preeminent sculptors.

Central to this cultural resurgence was a renewed focus on the natural and realistic depiction of the world. The importance of three-dimensional perspective became evident, exemplified by Michelangelo's iconic statue of David, consciously crafted for viewing from all angles—a departure from the two-dimensional sculptures of preceding eras meant solely for frontal observation.

This commitment to three-dimensional perspective extended to Renaissance paintings, with artists reviving ancient frescoes and infusing compositions with greater complexity. Human representation became more nuanced, emphasizing realism in depicting bodies and faces. The transition from tempera to oil paint during the Renaissance marked a pivotal moment, laying the foundation for the emergence of exceptional Dutch landscape paintings.

Raphael, like Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, emerged as a light of the Italian High Renaissance, embodying the essence of ideal Renaissance techniques and values. The period's continuing impact can be seen in its contributions to the advancement of artistic techniques and viewpoints, as well as its profound acceptance of humanism.

Mannerism (1520 – 1600): A Glimpse into the Emerging Aesthetic of Kitsch

Madonna With A Long Neck (1534-1540) By Parmigianino

The Mannerist period represents a distinct artistic movement that emerged in the aftermath of the High Renaissance. Historically situated amidst cultural and religious turmoil in Europe, marked by the Protestant Reformation and the Council of Trent, Mannerism signaled a departure from the classical balance and harmony of its Renaissance predecessors. The term "Mannerism" itself underscores an emphasis on style (maniera in Italian), reflecting a deliberate shift away from naturalism.

Prominent Mannerist painters, including Jacopo da Pontormo, Parmigianino, and Rosso Fiorentino, sought to break free from established norms. They intentionally distorted proportions, elongated figures, and experimented with unconventional compositions. This departure from Renaissance ideals is palpable in the unique features that define Mannerist art. Even Michelangelo, renowned for his contributions to the Renaissance, did not escape the influence of the exaggeration synonymous with the Mannerist era. Certain art historians argue that some of his later paintings deviate from the traditional Renaissance style.

Elongated proportions became a hallmark of Mannerist figures, creating an aesthetic characterized by elegance and sophistication.

The Mannerist color palette was both innovative and unconventional, featuring vivid and intense hues that contributed to the overall stylized effect. Symbolism played a crucial role, with Mannerist works incorporating allegorical elements that invited viewers to delve into deeper interpretations. Architectural distortion added to the movement's uniqueness, creating a sense of instability and challenging traditional perspectives.

Despite its departure from Renaissance ideals, Mannerism played a pivotal role as a bridge to the Baroque period. This movement paved the way for the exploration of emotion, theatricality, and dynamic compositions that would come to define the artistic landscape in the subsequent century.

Glorious Baroque Period (1590 – 1760)

Baroque Ceiling Frescoes (Ljubljana Cathedral)

Baroque art is known for its dynamic compositions, rich color palettes, and a sense of movement. Artists of the Baroque period aimed to engage the viewer emotionally, often using intense contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to create dramatic effects. The use of deep, vibrant colors, elaborate ornamentation, and intricate details defined Baroque artworks. Such artists as Caravaggio, Peter Paul Rubens, Rembrandt van Rijn and Gian Lorenzo Bernini became typical representatives of the Baroque period.

While the Baroque Era emerged as a reaction against the Mannerist style, there are notable connections between the two. Both movements rejected the classical ideals of the Renaissance, favoring a departure from balance and harmony. Mannerism, with its intentional exaggeration and distortion, set the stage for the dramatic and emotional qualities that became hallmark features of Baroque art.

The Baroque Era left an indelible mark on Western art and culture. Its influence extended beyond painting and sculpture to include architecture, music, and literature. The Baroque style's emphasis on emotion, theatricality, and a sense of grandiosity paved the way for subsequent artistic movements, shaping the cultural landscape well into the 18th century. The Baroque period laid the groundwork for subsequent artistic movements, influencing the Rococo and Neoclassical periods. The emphasis on emotion and movement persisted in the Romantic era, showcasing the enduring impact of Baroque aesthetics.

Beyond Baroque: The Rococo Art Period (1725 – 1780)

Greuze Jean-baptiste (1725–1805)

The Rococo period, which lasted from the early 18th century to the mid-18th century, arose as a playful and elaborate response to the grandiosity of the previous Baroque period. Characterized by its lightness, grace, and emphasis on decorative elements, Rococo art reflected the changing cultural and social landscape of Europe during this time.

Characterized by asymmetry, pastel colors, and intricate ornamentation, Rococo pieces often featured playful depictions of nature, charming scenes of courtly life, and imaginative, fantastical elements. Rococo themes often centered around love, romance, and pastoral scenes. Artists depicted idyllic landscapes, flirtatious encounters, and aristocratic leisure activities, fostering a sense of escapism and fantasy.

Return to Classical Principles: Classicism (1770 – 1840)

Angelica Kauffmann - Ariadne Abandoned By Theseus 1774

The Classicism period was distinguished by a return to classical principles and a renewed interest in order, symmetry, and logic in the arts. In response to Rococo's extravagant and fanciful excesses, Classicism drew inspiration from ancient Greek and Roman art, emphasizing clarity, proportion, and harmony. Classicism emphasized clear, well-defined forms, with meticulous attention to detail and precision in execution.

Unique Ingres, and Angelica Kauffman exemplified the era's commitment to classical aesthetics, producing masterpieces that celebrated heroic themes, mythological narratives, and the enduring beauty of ancient civilizations. Artists favored balanced compositions, often mirroring the classical ideals of ancient Greece and Rome.

Romanticism (1790 – 1850): Infusing Art with Profound Emotion

Karl Friedrich Lessing. "Knight's Castle On The Rock", 1828

The dates show that this artistic epoch happened about the same time as Classicism. Romanticism is frequently interpreted as an emotionally charged response to Classicism's severe demeanor. In contrast to the rigid and realistic nature of the Classicism period, Romantic paintings were far more emotive.

Romanticism was a cultural and artistic movement that emerged as a response to the rationality and order of the preceding Classicism. Characterized by a focus on emotion, individualism, and the sublime, Romanticism celebrated nature, imagination, and the expression of personal feelings in the arts. Romantic art prioritized emotion and personal expression, often exploring intense feelings, individual experiences, and the complexities of the human psyche.

Romanticism left an enduring legacy, influencing subsequent artistic movements, including Symbolism and Realism. Its emphasis on individualism, emotion, and the sublime laid the groundwork for a profound shift in artistic expression that continued to resonate well into the 19th century.

Realism Period (1850 – 1925): The Age of Objectivity

Proudhon And His Children (1865) By Gustave Courbet

The Realism art period marked a significant departure from the idealized and romanticized depictions of the preceding Romantic era. Rooted in the pursuit of truth and objectivity, Realism sought to portray ordinary life with precision, emphasizing the everyday struggles and experiences of common people.

Characterized by a focus on accurate representation, Realist artists sought to capture the details of their subjects with meticulous attention. Scenes from urban life, rural landscapes, and the industrial revolution became prominent themes. Realism rejected the fantastical and instead embraced the tangible realities of the contemporary world.

Among the notable artists of the Realism period is Gustave Courbet, considered a pioneer of the movement. His painting "The Stone Breakers" exemplifies the Realist commitment to portraying the harshness of labor and the lives of the working class. Jean-François Millet, another influential figure, depicted rural life in works like "The Gleaners," showcasing the dignity in everyday tasks.

Honore Daumier, famous for his satirical and socially critical works, used his art to comment on the political and social issues of his time. His caricatures and paintings, such as "The Third-Class Carriage," provide a candid portrayal of contemporary society.

Realism laid the groundwork for later movements such as Naturalism and Impressionism, influencing the trajectory of art well into the 20th century. Through its commitment to depicting reality without embellishment, the Realism art period remains a crucial chapter in the evolution of artistic expression.

Impressionism (1850 – 1895): The Dawn of Modern Art

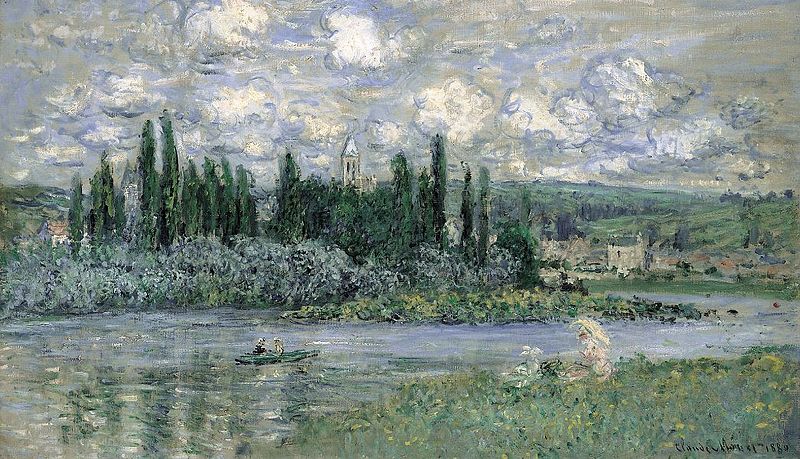

Claude Monet Vétheuil Sur Seine 1880

The Impressionism art movement represents a transformative departure from traditional artistic norms. This revolutionary approach, characterized by its emphasis on capturing the immediate effects of light and atmosphere, sought to convey the essence of a scene rather than its meticulous details.

Impressionist painters employed distinctive features to achieve their vision. Artists embraced visible and loose brushstrokes, creating a sense of movement and immediacy in their works. Outdoor painting, also known as en plein air, became popular because it allowed artists to immediately capture changing light and ambiance, resulting in more spontaneous works. Everyday scenes, landscapes, and urban life emerged as popular subjects, each approached with a fresh and unconventional perspective.

Central figures in the movement include Claude Monet, whose "Water Lilies" and "Impression, Sunrise" exemplify the commitment to capturing light and color play. Edgar Degas brought dynamism with scenes of ballet dancers and horse races, seen in "The Dance Class" and "Racehorses at Longchamp." Pierre-Auguste Renoir focused on human interactions and joyous moments in works like "Luncheon of the Boating Party."

The role of galleries was pivotal in the acceptance of Impressionist art. Initially rejected by traditional institutions, artists organized independent exhibitions, like the Salon des Refusés, showcasing their works outside the official establishment. As public interest grew, established galleries recognized the commercial potential, contributing to the wider acceptance of Impressionism and its lasting impact on modern art's trajectory. This movement laid the groundwork for subsequent artistic developments in the 20th century.

Symbolism Period (1886 – 1900): Meaning in Art

“the Demon Seated ” (1890) By Mikhail Vrubel

The Symbolism painting movement broke away from the realist and naturalist methods that dominated the artistic scene. Symbolism emerged in France during the late 19th century, gaining prominence in the 1880s and extending into the early 20th century. The movement was a reaction against the prevailing artistic styles of the time, particularly the realism and naturalism that dominated the art scene.

Symbolism, characterized by its emphasis on symbolism, spirituality, and the exploration of the mystical and subconscious, quickly gained traction and spread across various artistic disciplines, including painting, literature, and music. The movement's influence extended beyond France, impacting artists in other European countries and shaping the cultural landscape of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Artists found themselves captivated by the expression of emotions and ideas through the medium of objects. Common themes within the Symbolism movement encompassed concepts like death, sickness, sin, and passion. Notably, the predominant use of clear forms during this period is thought to foreshadow the upcoming Art Nouveau era, according to art historians.

Embracing Expression Beyond Naturalism: Post-Impressionism Period (1886 – 1905)

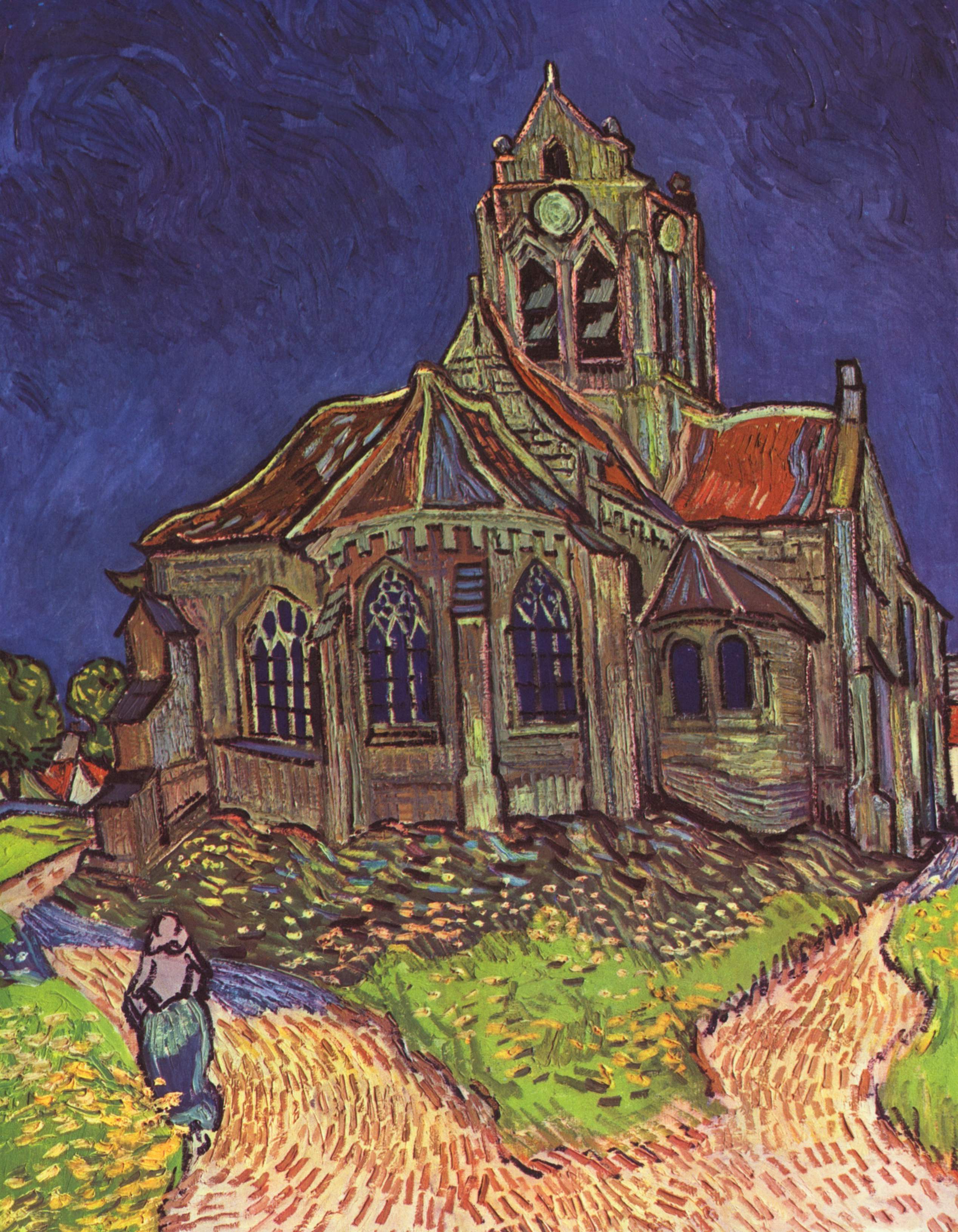

Church At Overy Vincent Van Gogh 1890

The post-Impressionist era emerged as a departure from the preceding Impressionist movement, challenging the confines of Naturalism in color representation and expression. Coined by 20th-century art critic Roger Fry in 1910, the term encapsulated the evolution of art beyond Édouard Manet's stylistic propositions. Post-Impressionism, in contrast to its predecessor, embraced profound symbolism, transcending mere optical impressions derived from nature.

This revolutionary time was handled by well-known post-Impressionist artists such as Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Cézanne. While each artist operated independently, their works shared a departure from Impressionist norms, cultivating a more emotionally charged atmosphere. Georges Seurat, for instance, crafted a distinctive painting style, while traditional mediums underwent innovation, setting these artists apart in the early 20th-century art scene.

Notably, the influence of post-Impressionists extended to the famed Fauvists, with artists like Henri Matisse drawing inspiration from luminaries such as Paul Signac and John Russell. The interplay of styles and techniques during this period fostered a dynamic and influential art movement that left an indelible mark on the trajectory of modern art.

Art Nouveau (1890 – 1910): Klimt's Shining Epoch

Gustav Klimt "The Kiss" (1907–1908)

Gustav Klimt, a well-known Austrian painter, was a crucial figure in the Art Nouveau movement, making an unforgettable impression with his unique style and inventive approach to painting. Klimt, a major player in the Vienna Secession, a group of artists who attempted to break free from traditional academic art, became identified with Art Nouveau's extravagant and decorative aesthetics. Klimt developed a highly distinctive style characterized by intricate ornamentation, symbolic motifs, and an emphasis on decorative elements. His works often featured elaborate patterns, gold leaf, and intricate details, reflecting the opulence of the Art Nouveau movement.

Overall, Art Nouveau differs from previous styles in that it emphasizes organic shapes, detailed details, symbolic meaning, and the integration of art into everyday life.

Expressionism Period (1890 – 1914): Art as Political Commentary

Wassily Kandinsky, 1903, The Blue Rider

In the realm of Expressionism, the resurgence of subjective feelings takes center stage, originating in Germany and serving as a platform for artists to critique prevailing power dynamics. Unlike Naturalism or exterior appearances, Expressionist artists focused on internal feelings, imbuing their works with a sense of ferocity and archaic expressiveness. Wassily Kandinsky, a notable Modern artist, embraced Expressionism in his abstract compositions, utilizing it as a means to explore color theory, form, and the essence of pure abstraction in painting.

As the First World War unfolded, Expressionist paintings took on a disturbing intensity, becoming a potent vehicle for direct political messages and reflecting a sense of violence in brushwork styles. The distinctive features of Expressionism lie in its unapologetic emphasis on subjective emotion, rejection of external realism, and a willingness to convey powerful political and social messages through intense and often confrontational artistic expression.

Cubism (1906 – 1914): The Art of Distorted Realities

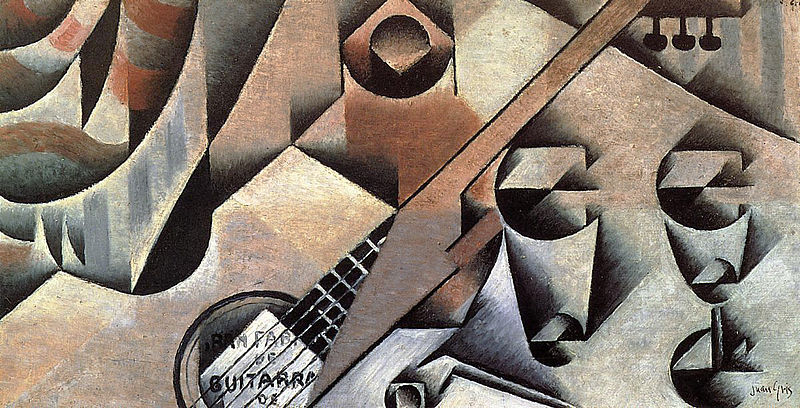

Juan Gris, 1912, Guitar And Glasses

Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in the early 20th century, revolutionized artistic representation. Characterized by geometric abstraction, the movement broke down objects into fragmented forms, portraying multiple perspectives simultaneously. Cubist artists depicted subjects through interlocking planes, challenging traditional spatial conventions. The movement evolved into Analytical Cubism, marked by monochromatic compositions, and later, Synthetic Cubism, incorporating vibrant colors and collage elements. Cubism extended its influence to sculpture and applied arts, reshaping artistic boundaries. Picasso and Braque's collaboration birthed a movement that not only transformed visual representation but also laid the groundwork for subsequent abstract art movements in the 20th century.

Futurism Period (1909 – 1945): The Anarchic Wave in Art

The City Rises By Umberto Boccioni 1910

Futurism, initiated by Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1909, sought to capture the dynamism of the modern world. Artists like Giacomo Balla and Umberto Boccioni were pivotal in this movement. Characterized by an embrace of technological progress, speed, and urban life, Futurism rejected traditional artistic norms. The movement glorified war, portraying it as a cleansing force and an opportunity for renewal. It celebrated industrialization and envisioned a future shaped by machines. Notably, the Futurists drafted manifestos to articulate their revolutionary ideas, and their dynamic approach influenced diverse art forms, including painting, sculpture, literature, and performance. Futurism's distinct blend of anarchic energy and avant-garde enthusiasm left an enduring impression on the art of the 20th century.

Dadaism (1912 – 1920): Nonsense as a Revolutionary Artistic Language

Marcel Duchamp "Nude Descending A Staircase" 1912

Dadaism, a radical movement that emerged in the aftermath of World War I, represents a defiant rejection of traditional artistic and societal norms. Pioneered by artists like Marcel Duchamp and Tristan Tzara, Dadaists sought to dismantle established conventions, embracing chaos, absurdity, and anti-art sentiments. The movement deliberately rejected reason, leading to the creation of artworks featuring nonsensical compositions, collages, and performances. Dada, a term randomly chosen from a French-German dictionary, encapsulates the essence of irrationality and absurdity that defines the movement. Dadaism's legacy lies in its subversion of artistic norms, influencing subsequent avant-garde movements such as Surrealism and performance art.

Constructivism (1913 – 1930): Bridging Cubist Forms with Futurist Dynamics

Blue Counter-relief, 1914, Vladimir Tatlin

Constructivism, flourishing from 1913 to 1930, was an avant-garde movement that originated in Russia. Rejecting traditional art forms, Constructivists embraced the integration of artistic and industrial design, seeking practical and socially relevant applications. Pioneered by artists like Vladimir Tatlin and Aleksander Rodchenko, Constructivism aimed to bridge art with everyday life. The movement's hallmark was the use of geometric forms, industrial materials, and an emphasis on functionality. Constructivist artworks often included architectural models, graphic design, and innovative use of space, reflecting the utopian ideals of the Russian Revolution. This dynamic movement aimed to construct a new visual language, emphasizing collaboration and the intersection of art, technology, and social progress. Its influence extended beyond Russia, impacting modernist design and architecture worldwide.

The Harlem Renaissance (1920 – 1930): A Renewal of African-American Artistic Expression

The 1920s saw a significant cultural renaissance among African-American communities in America, known as the Harlem Renaissance. This momentous decade saw the rise of intellectual and cultural expressions in a variety of art genres, including music, literature, visual art, poetry, politics, dance, and fashion, all coordinated by African-American visionaries. This period, also known as the New Negro Movement, included distinct modern art styles that told the Black experience from a non-Western perspective, an important response to the historical neglect of African-American educators and artists.

Harlem, a vibrant New York neighborhood, served as the epicenter of this cultural renaissance, giving rise to influential figures who championed African-American culture in the early 20th century. Beyond artistic expression, the Harlem Renaissance instilled a robust commitment to political activism, leaving a lasting impact on subsequent movements like the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s.

Surrealism (1920 – 1930): Reality Defied

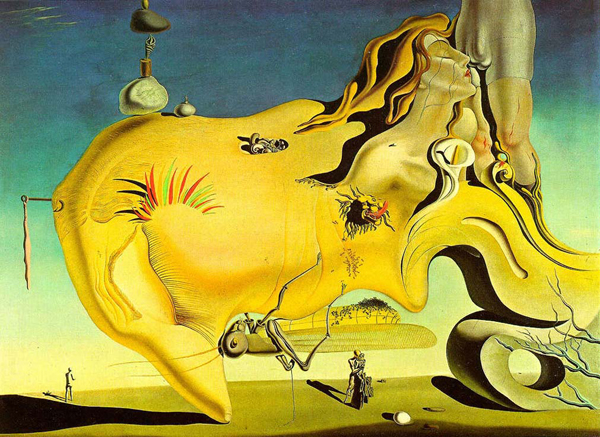

"The Great Masturbator" Salvador Dali 1929

Rooted in the aftermath of World War I and influenced by Dadaism's anti-rationalism, Surrealism embraced spontaneity, free association, and automatism in artistic creation.

Harboring a fascination with the bizarre and fantastical, Surrealism featured distorted, dreamlike imagery and explored the depths of the human psyche. Salvador Dalí, a prominent Surrealist artist, captured attention with his melting clocks and eccentric symbolism. Emerging in Europe, especially in Paris, Surrealism aimed to liberate the mind from societal constraints and embraced the irrational as a means of expressing deeper truths. The movement left an enduring impact on art, literature, and thought, extending beyond its initial temporal confines.

New Objectivity (1925 – 1965): The Precision and Coldness of Art

"The Triumph Of Death" Otto Dix 1934

New Objectivity, emerging in the aftermath of World War I, rejected idealism and embraced a cold, technical realism. Flourishing between 1925 and 1965, this movement captured the starkness of post-war Germany. Artists like Otto Dix and George Grosz depicted the harsh realities of society with precision, focusing on everyday scenes and societal disintegration. The style embraced a detached, objective view, reflecting the disillusionment and skepticism of the time. New Objectivity was marked by its rejection of emotionality in favor of a clinical portrayal of societal and political issues, offering a stark contrast to the expressive styles of the preceding decades.

Art's Evolution Beyond European Boundaries: Abstract Expressionism (1948 – 1962)

Canticle Mark Tobey 1954

The 1960s witnessed the profound impact of Abstract Expressionism, a groundbreaking art movement that emerged post-World War II. This period saw a shift from traditional painting, as American artists experimented with abstract techniques to portray emotion. Notably originating outside of Europe, Abstract Expressionism found its roots in North America, emphasizing color-field painting and action paintings. In a departure from traditional methods, artists like Marc Tobey and Jackson Pollock eschewed brushes, opting to pour buckets of paint on the ground and using their fingers to craft images.

Pioneered by influential figures of the 1960s, including Tobey and Pollock, Abstract Expressionism introduced a novel technique where paint was applied so thickly that the finished piece took on a distinctive form, unlike any painting that came before it. However, amidst its revolutionary spirit, Abstract Expressionism faced criticism, particularly during the Cold War era, with some conservative Americans deeming it "un-American." This period not only revolutionized artistic techniques but also sparked debates about the role of art in reflecting national identity and values.

Pop Art (1955 – 1969): Where Everything Becomes Art

Pop Art originated in the mid-1950s in the United Kingdom and the United States, emerging as a response to the prevailing abstract expressionist movement. The movement found fertile ground in the urban environments of New York and London, where artists sought to incorporate popular culture and mass media into their works. For Pop art artists, practically every part of popular culture in everywhere was art. Photorealism and serial printing impacted painting and graphic arts.

Characterized by bold colors, repetition, and a sense of irony, Pop Art transformed everyday objects into artistic statements, blurring the lines between high and low culture. It remains an important movement in contemporary art, reflecting the vibrant and dynamic nature of post-war society. Rejecting traditional elitism, artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein embraced imagery from mass media, advertising, and consumer products. Renowned for Warhol’s iconic Campbell's Soup Cans and Marilyn Monroe portraits, Warhol was a central figure in the Pop Art movement. His studio, "The Factory," became a hub for artistic innovation.

Neo-Expressionism (1980 – 1989): A Contemporary Echo of Fauvist Spirit

In the 1980s, the art world witnessed the emergence of Neo-Expressionism, marked by the creation of expansive, representational paintings with a life-affirming essence. Berlin served as a pivotal hub for this movement, where artists often depicted the dynamism of cities and urban life. The term "Neo-Expressionism" drew inspiration from Fauvism, and although the Berlin group disbanded in 1989, a number of artists continued to carry the torch in New York, perpetuating this distinctive style.

Art, as a cornerstone of human experience, transcends mere aesthetics. It serves as a profound means of expressing the complexities of our human existence, capturing both the challenges and joys that define our lives. This brief exploration of the art periods timeline aims to offer a glimpse into the rich contexts that surround some of the most celebrated works of art, emphasizing the enduring role of artistic expression in illuminating the human experience.

No Comments Yet...